Chapter 9

Available as e-book

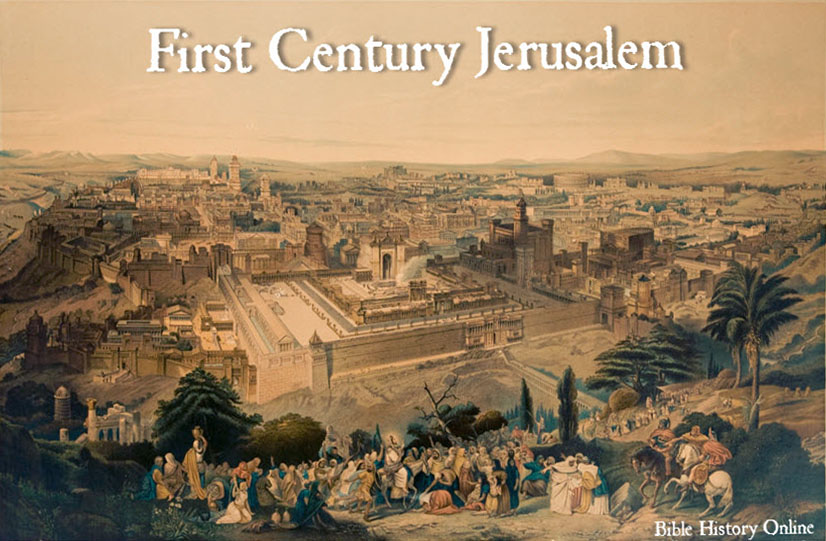

Christian New Testament

Galatians (1:18)

I went up to Jerusalem to get acquainted with Peter and stayed with him fifteen days.

GIFTS TEMPT EVEN THE GODS

[Euripides]

A fictitious story may one day become a reality when made into a PLAY/MOVIE with flesh and blood characters. [Copyrights still available]

July 21, 2014: Review of Frank Wilson

book editor of The Philadelphia Inquirer

Olga and I have been corresponding off and off since I was The Inquirer’s book editor. Recently, we started corresponding again, and she told me about The Blue Mirror and hoped that someday I might read Chapter 9, which I take it she regards as central to the novel. So I got a copy on my Kindle and did precisely that. I’m glad I did. I found it to be a very good presentation of evidence and argument in support of a point of view regarding the early development of Christianity that is both factually sound and imaginative. It doesn’t just follow through on Paul’s admonition to think of these matters. It also reminds the reader of what those things are—specific, crucial details that from casual usage over time have been worn down to cliché.

The chapter demonstrates how such matters can benefit from a conversational presentation, and the fictional dimension underscores the ambiguity of the subject. Antonio is nothing if not confident his evidence is sound and his arguments well-framed. The young woman he is talking to is very taken with him and with what he has to say.

But he is not only a character in a fiction, he is also spinning a tale, about how Paul managed to persuade Peter that Gentiles ought to be allowed to become followers of Jesus without first becoming Jews. Antonio makes it into a domestic comedy, with Peter’s wife brokering the deal. Antonio’s irreverence, by being so down-to-earth, makes his account seem all the more plausible.

In fact, it is because this chapter works as fiction that it works as exposition. Fiction can open a door to discussion and, by means of ambiguity, leave it open. Antonio touches upon a good deal more than what was decided at the Council of Jerusalem. There is the business about the Egyptian god Osiris and the notion of resurrection, which reminds the reader that Judaism almost certainly owes something to the Egyptians who had enslaved them. Similarly, Antonio’s reference to the Septuagint should bring to mind thoughts about the connection between Judaism in Alexandria and Jerusalem.

Perhaps the most interesting exchange in the chapter comes at the very end. “It seems that our ancestors had much common sense,” our heroine says. “They used it”, Antonio replies.

Yes, our ancestors were responding to the world as they experienced it, and they did not experience it from a modern scientific viewpoint. Chapter 9 works because it encourages us to see matters from our ancestors’ point of view, rather than to see that point of view as a benighted version of ours.

Antonio’s point of view is persuasive, but like all such points of view, including my own, not decisive—the deciding factor is whatever catalytic agent serves to trigger an act of faith. This Chapter 9 introduces the reader to all sorts of fresh perspectives, but doesn’t really insist on any of them, leading the reader to think on them independently.

Creativity is the ability to grasp the essence of one thing, and then the essence of some very different thing, and mash them together to create some entirely new thing.

EINSTEIN:

Logic can bring you from A to B Imagination will take you EVERYWHERE

Wittgenstein:

We live in a linguistic world where REALITY is what we construct in words