Without darkness LIGHT has no definition

LIGHT without FIRE

From campfire TALK to MASS SPEECH on the Internet

Writing is the graphic expression of actual SPEECH

The pen is the TONGUE of the mind (Horace)

Long before people TOLD STORIES of being abducted by aliens,

they TOLD STORIES of being visited by angels, or gods, or demons

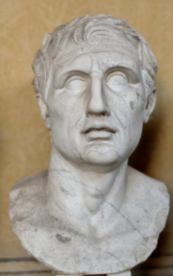

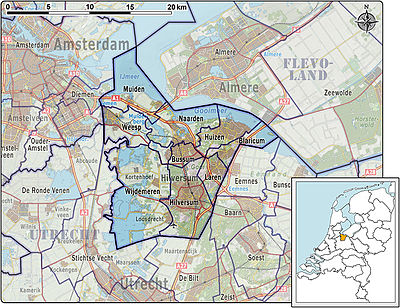

THE MYSTERY OF THE MISSING PORTRAIT

[A Brain Teaser]

Copyrights Olga Pitcairn

PS 363 YEAR 2020

WALLFLOWERS AND BLUE FORGET-ME-NOTS

PS 363---YEAR 2010

Missing portrait of

Cees (Cornelis) Jonkheer

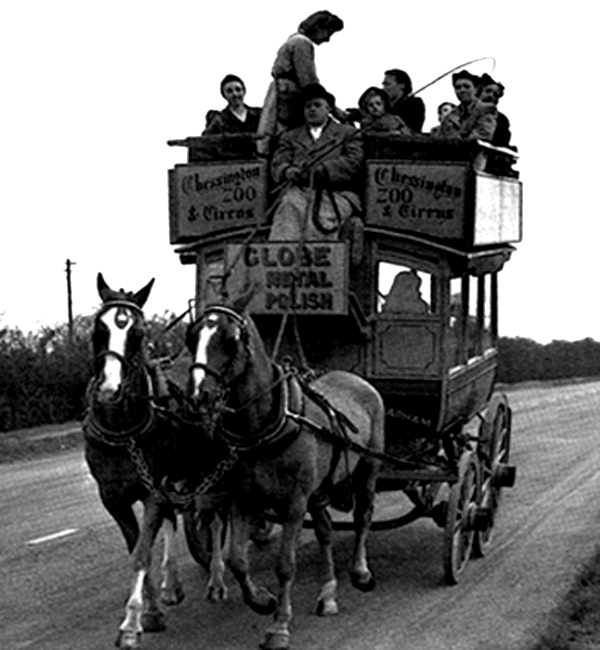

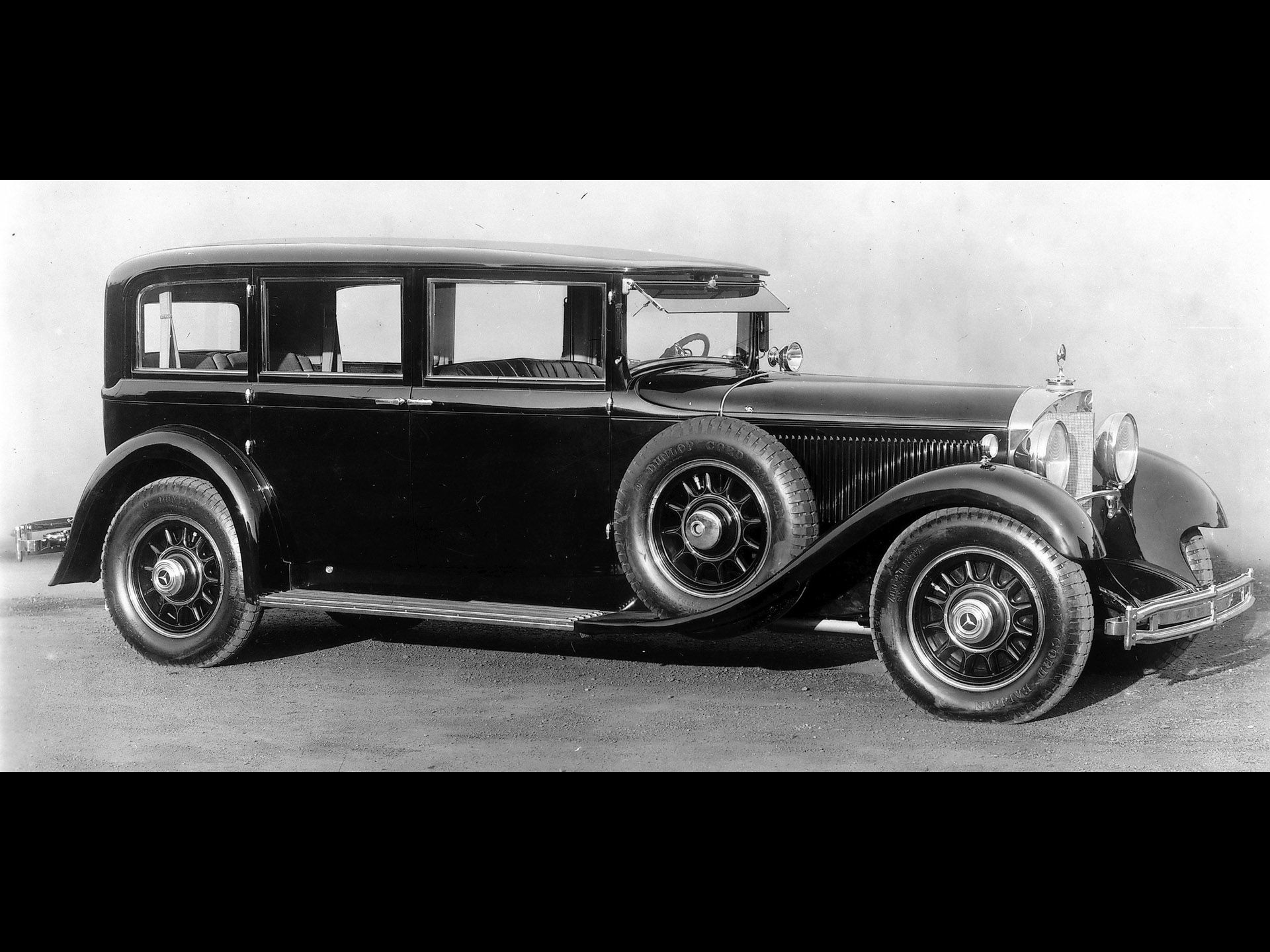

Hansom cab

Barouche Landau

OMNIBUS

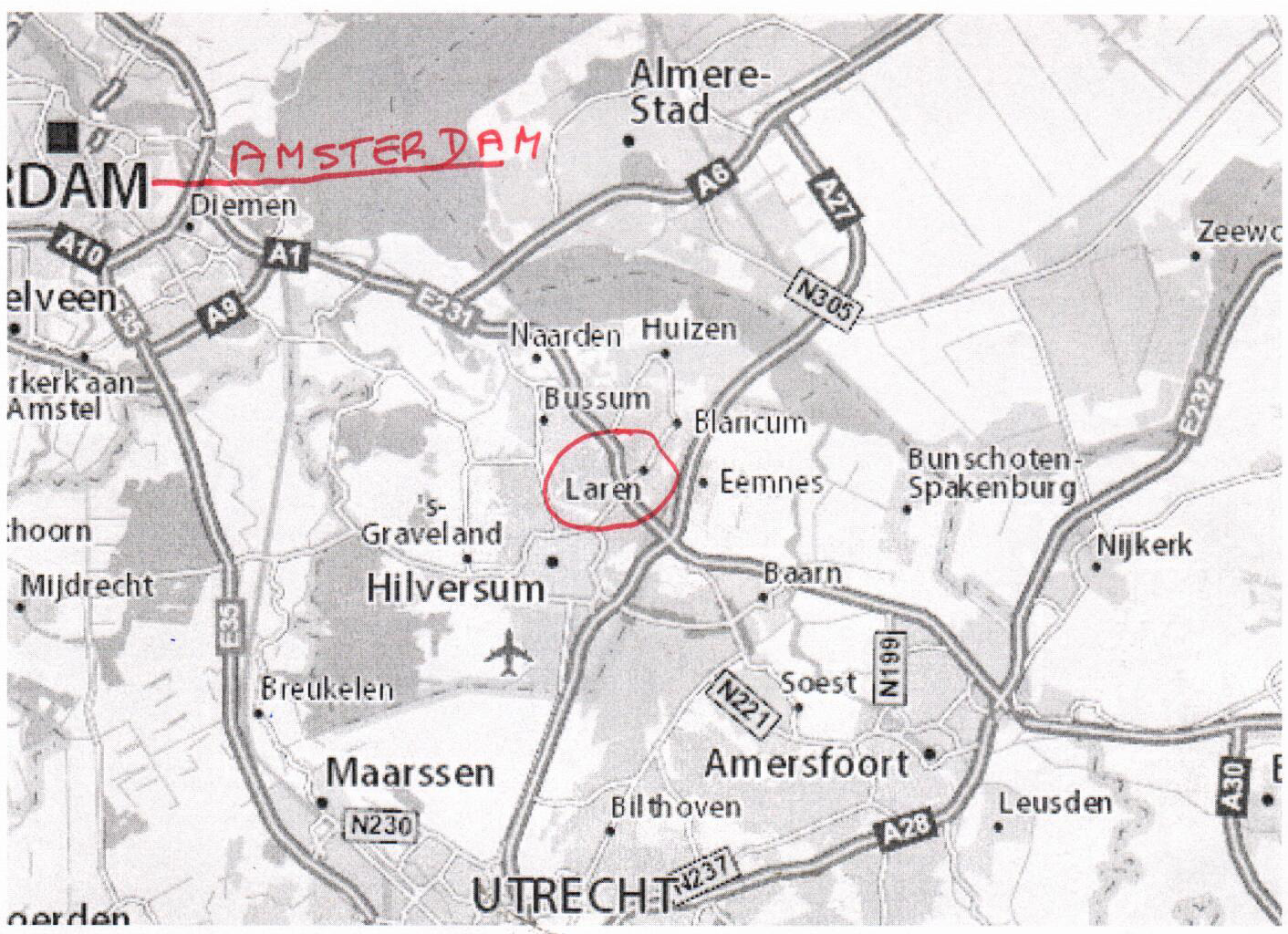

NETHERLANDS / HOLLAND

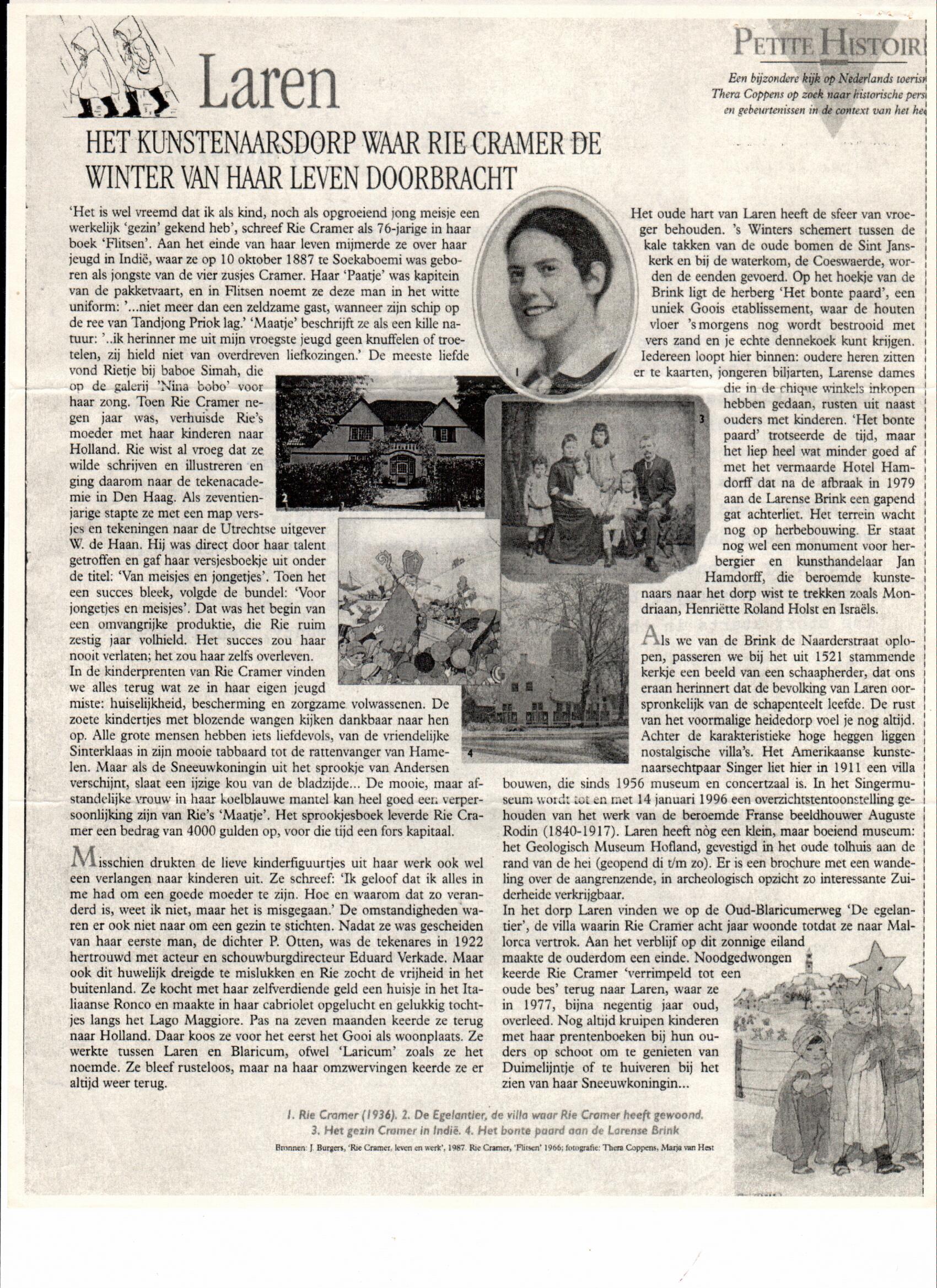

LAREN 't GOOI

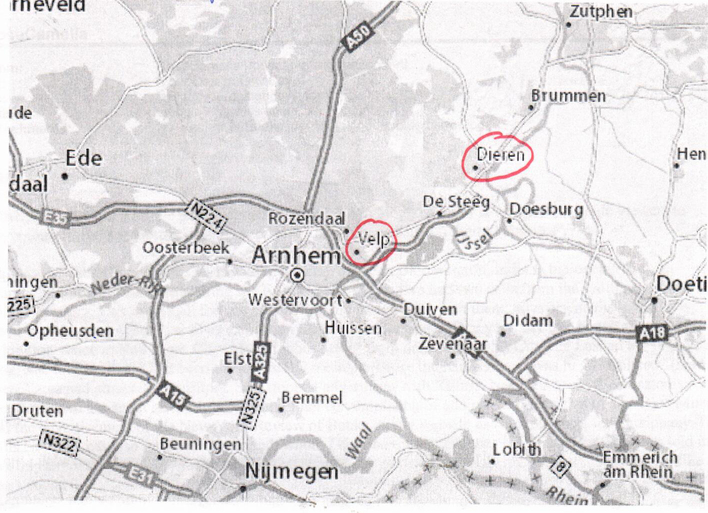

ARNHEM / VELP / DIEREN

DIEREN / ZUTPHEN / LAREN

VELP, the Netherlands

Christmas 1910: Cees Jonkheer promised his son Anton (born Christmas 1885) for his 25th birthday a trip to Paris.

PARIS, Hotel MONNIER, May 1911

Anton Jonkheer looked at the train ticket for his return home—Paris/Brussels/Amsterdam—and, smiling, put it in his coat pocket. Concierge Pieter Goudsmit hailed a Hansom cab and bade Mr. Jonkheer “Tot ziens en goede reis” (Farewell and safe travels).

Upon arrival in Amsterdam Anton went straight to the offices of Het Laatste Nieuws on Kerkstraat. At the reception desk he asked to see the editor. The clerk told him his boss was out of town. Anton asked for a job application form.

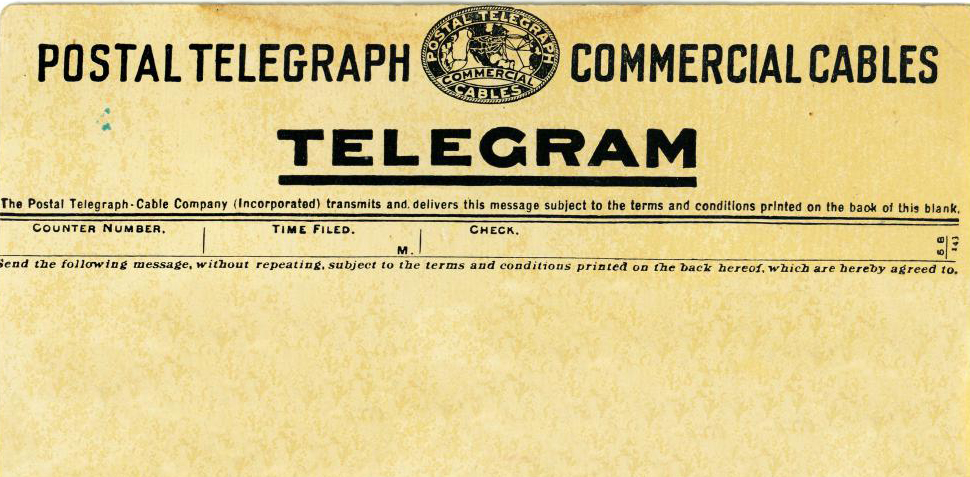

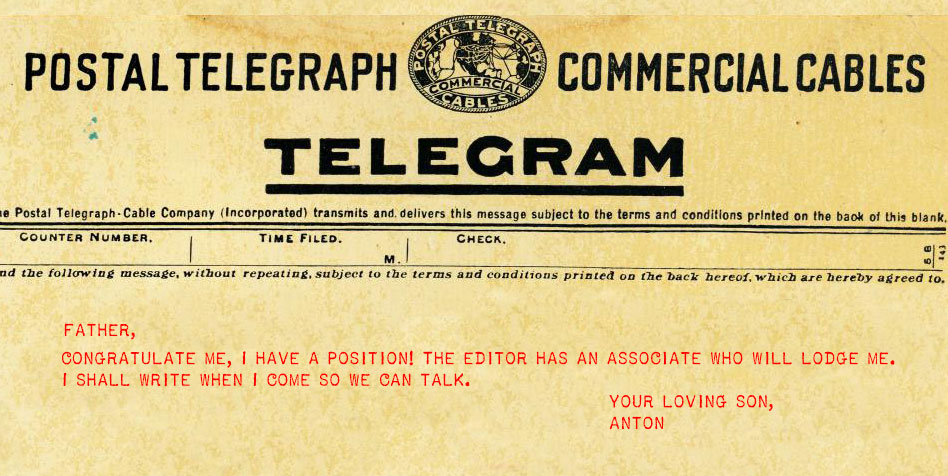

Eager to see his father, Anton sent a telegram that he would take the train to Arnhem the next day, arriving late afternoon. He spent the day in his hotel; writing an article on French authors he intended to submit with his résumé to the editor.

When Anton entered Centraal Station a porter took his valise, and they headed for the train to Arnhem. The conductor took him to his seat in a compartment. A young man stood up and introduced himself as Leopold Moojer, known as Leo; his family had their roots in Almelo, Overijsel. Anton said his family resided in Velp, Gelderland, but their roots were in Den Bosch, Brabant.

Smiling, they settled in their seats across from each other.

Anton gave Leo the low down that he had just returned from Paris. He wanted to be a journalist working for Het Laatste Nieuws. He had two older brothers and a much younger sister, Cornelia; the family called her Nel. His father was a military man and until his retirement had been stationed in Java, the Indies; that’s where he, Anton, was born.

Leo informed Anton that he worked for a real estate agency in Arnhem; that his father was a police constable, and that he and his sister Dina were the youngest of eight children. He had been visiting his sister, who was married to a book-keeper at an insurance company where he once also worked. Nicodemus, his brother-in-law, had asked to rent them for the summer a cottage in Gelderland.

Formalities settled, the young men had a lively conversation about life in general. They exchanged addresses. Leo promised to visit Anton soon.

The train arrived in Arnhem. On the platform the young men shook hands firmly. Hans, the Jonkheer’s family coachman, took Anton’s valise. Leo waved as the barouche landau left direction Velp.

The carriage stopped at Villa Amourette in the Annastraat across from park Larenstein. Hans took the valise down and informed Anton that Mrs. Jonkheer and Miss Nel had left for Den Haag. Cook had made dinner. His father was in bed with a cold and wished to see him right away.

Worried, Anton dashed upstairs. He called out that he was home and entered the bedroom. Cees was in bed propped up between pillows: a large blue silk scarf around his neck hid his beard and a fluffy white night cap crowned his head. Anton rushed into his father’s outstretched arms. He took the cap, ruffled his father’s white-streaked black hair, and planted a smacking kiss on his pate. He replaced the cap and confessed that he was glad to be home. Cees laughed as he took his son’s hands to squeeze them. Then he bid him to have dinner alone. Anton should tell him about the City of Light after breakfast.

Anton arose early. He went to the walnut wardrobe in his bedroom and opened it. He chose a gray-checked suit. As he combed his black hair, he scrutinized himself in the mirror above the wash-stand. “The spitting image of Father except for the beard,” he whispered, his brown eyes shining. “Maybe I’ll grow a moustache?”

Tall and lanky, Anton looked dapper when he dashed downstairs for breakfast. Cook’s specialty was a waffle-grilled ham and cheese sandwich. He had two. She let the cat out of the bag that Miss Nel had been courted by an unsuitable young man and Mrs. Jonkheer decided to take her to relatives in Den Haag for a change of scenery. Out of sight, out of mind was the motto.

It was a clear day and Anton walked to the bus stop on Hoofdstraat. The privately owned horse-drawn omnibus started at Arnhem and on to Velp/Rheden then to Doesburg/Westervoort and back to Arnhem. Anton got out at Rheden. He took the road to Dieren on foot to Boerenplezier, the family’s farm.

Hans was in the stable. He inquired about Anton’s trip; who replied he had a fantastic time. Then Anton broached the subject he came for—about boarding a poor young artist, a painter born in Zwolle. When he was a child his parents went to Paris. The painter’s name was Phlip Goudsmit. Hans smiled broadly, saying he had a cousin living in Zwolle; perhaps he would know some Goudsmit relatives. Nodding, Hans said Phlip was welcome. He got the carriage ready and drove Anton to Villa Amourette; then took Cook to the market.

Cees sat in his cherry-red velvet Victorian wingchair when Anton entered the sun-filled parlor. Drawn velvet curtains, an attractive shade of salmon, showcased—center stage window—a large gilded bird cage. As soon as it saw Anton, the yellow parrot cackled. Cees held out his arms. After a warm embrace, he pointed to the chair nearby; it fronted a table with a coffee pot, sugar bowl, creamer, and two cups and saucers as well as a plate with stroopwafels.

“Anton,” Cees took a handkerchief from the pocket of his charcoal gray hand-knitted cardigan that enhanced his silvery beard, “tell me about your escapades.”

“Let’s have coffee first.” Anton eyed the home-made cookies. He gave his father a steaming cup.

A twinkle in his brown eyes, Cees sipped as he watched Anton eat with gusto. He put his cup on the small table next to his chair and took a stack of cards. “Thank you, son, for sending me these wonderful memories.” He held up a postcard of the Eiffel Tower. “Paris! The City of Light!” Ceese’s face lit up as well. “I’m eager to hear about all the wonders you encountered.”

Anton reached for the postcard. “The City of Light, indeed,” he gushed. “Those French invented a wonderful new way of living at night. Father, you should see the boulevards and the monuments when lit up! This city is like a huge cabaret with people dining outdoors and dancing in the parks.” Anton waved the Eiffel postcard. “This emblem is their beacon. It was the entrance to the 1889 Paris World Exposition.” He took a deep breath. “But I’ve been told that it commemorated the 1789 centennial of their bloody revolution. This beacon is a marvel when lit like a Christmas tree.” He put the postcard on the coffee table.

“You know that I wanted to visit the home of my favorite author, Stéphane Mallarmé?” Cees nodded. “So I paid homage and went to Rue de Rome. I stood there in awe, thinking of his influence on me; on how to use words; that words have a meaning.”

Anton reached for the postcards his father was holding. He took a card and held it up, laughing. “This is a portrait of Debussy. He set to music Mallarmé’s poem Afternoon of a Faun.”

“Of course you attended the concert?” Cees smiled.

“Of course, Father! It was memorable. And I made up my mind to become a literary journalist.” He went to the bird cage. Holding up a wagging finger, Anton crooned, “Queenie! Queenie! Tell Nel that I have applied for a job at Het Laatste Nieuws in Amsterdam!”

Loud clapping filled the parlor. The parrot cackled.

Anton returned to his chair, clapping softly.

Cees beamed. “Son, congratulations!”

“Well . . . I still have to fill out my job application,” Anton confessed. “I decided to include an essay on French authors, so the editor knows I’m serious.”

“French authors?” Cees leaned forward.

“I thought of Victor Hugo. He wrote Les Miserables. And of course Balzac, who was an expert on human nature. And also Flaubert; Madame Bovary is still a big hit with the ladies.” Anton chuckled. “It was considered pornographic because she wasn’t hiding her adultery.”

“How about Emile Zola. He wrote a letter about that dreadful Dreyfus Affair.” The military man was visibly agitated.

“That letter, J’Accuse, made Zola famous.” Anton nodded. “He was a defender of the down-trodden. I admire Zola. He was a true journalist and a great critic. I hope I can step into his footsteps. Zola . . .” Anton hesitated, “wrote Nana. I don’t think I have talent for writing novels.”

Anton took a postcard and gave it to his father. “This is Hotel Monnier where I was staying. Henri Monnier was a famous caricaturist. Our concierge, Pieter Goudsmit, guess what, Father,” Anton chuckled, “Pieter was born in Zwolle! Well, he got me a theater ticket for the play Joseph Prudhomme.”

“What was it about?” Cees stroked his silvery gray beard.

“Oh . . . about the quintessential “citizen”. Joseph was of course pictured clownish so the audience could laugh without being embarrassed. I’m sure they saw in him their neighbors, and hopefully themselves.” Anton grinned. “Indeed, Monnier was a word painter, colorfully describing the bourgeois period.” He put the stack of cards on the table. “More coffee, Father?”

Cees gave him his cup. As they were sipping, Anton blurted out, “Father, I promised Pieter Goudsmit to ask you if his son Phlip, a young painter, can stay at Boerenplezier. Hans said Phlip is welcome if you agree.”

“How can I refuse?” Cees said with a wink. “What’s Phlip like?’

“I haven’t met him, so I can’t tell you what he’s like. His father said Phlip wants to paint Dutch scenes.”

“Cook told you about,” Cees smiled, “Mother and Nel visiting relatives in Den Haag?” He winked. “Most likely they won’t return until August. The young man must come soon. Send a telegram, son.”

Relief showing in his face, Anton got up and gave him a warm hug. “I’ll go to the post office right away.”

Anton went to the kitchen. He left a note for Cook that he would not be having lunch; he was going to Arnhem. Then he ran upstairs to his room and got Leo’s address.

Whistling, Anton walked to the bus stop. In Arnhem he went to the post office. He sent the telegram to: Goudsmit, c/o Hotel Monnier, Paris. Phlip welcome mid June. Confirm arrival to Leo Moojer, Makelaar Tom Gelder, Arnhem. Signed Anton Jonkheer.

Still whistling softly, Anton entered the office of Makelaar Tom Gelder. Leo jumped up from his chair and smiling broadly welcomed him with a warm embrace. Anton suggested having lunch at restaurant De Schimmel. As they were eating veal croquettes with mustard sauce, their specialty, Anton told him to expect a telegram from Paris regarding the arrival of a young painter by the name of Phlip Goudsmit. The artist would stay at Boerenplezier, the family’s farm near Dieren. Then Anton invited Leo for coming Sunday lunch at Villa Amourette.

When the two parted, they were beaming. Leo quickstepped direction office and Anton, looking at his watch, walked toward Velp. On the way he bought the local newspaper. Arriving at park Larenstein, he sat on a bench. When he finished reading the paper he crossed over to Annastraat.

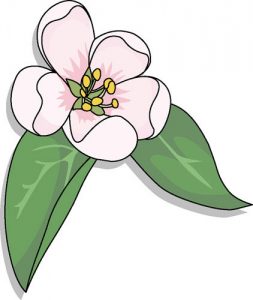

Anton entered the front yard of Villa Amourette. The apple trees were in full flower. As he strolled up the path, he sniffed the air, enjoying their perfume. He opened the front door and stepped inside.

Cees was in his wingchair reading a newspaper when Anton entered the parlor. “Son,” he put the paper on his lap, “what have you been up to! Cook is curious to know what you had for lunch in Arnhem.”

Grinning, Anton gave his father a smacker on his head. The parrot cackled. Anton went to the chair next to the cage. The bird moved to be near Anton when he sat down. “Queenie,” he whispered, “I had lunch with a handsome young man and we ate delicious croquettes.” The parrot hopped around the cage, cackling its heart out. Anton reached for a jar on the window sill and took out a nut. Queenie flapped her wings and rushed up to get her treat.

Anton went to the chair across from the coffee table and sat down.

Cees wagged a finger when he said, “Croquettes? That spells De Schimmel! How long have you known this handsome young man?”

“We met on the train. He was visiting his married sister in Amsterdam.”

The parrot cackled and screeched, “Fiepjes! Fiepjes!”

Anton got up and gave Queenie one more nut, saying that if she again interrupted— he stuck out his tongue like Nel always did— he would cover her cage with the lace cloth, he pointed, that was neatly folded on the window sill. He returned to his chair.

“His name is Leopold Moojer. The family is from Almelo. Leo works in Arnhem at Makelaar Tom Gelder.”

Waving the paper, Cees rose from his chair. “What a coincidence! The father sold me Villa Amourette when I married Mother! She fell in love with the name. The house needed repairs but the garden was a delight.” He sat down. “We never regretted living here.” Cees slowly folded the paper. “Now, Anton, go ahead and tell me what you were contriving with handsome Leo.”

“I told him about the telegram I sent. And that Phlip will contact him when he would arrive in Arnhem. Hans will then fetch him.”

“Tell Hans to bring him straight to Boerenplezier.” Cees shook his head. “We’ll meet later.”

“Father, I invited Leo over for Sunday lunch. I thought you would like to meet him.”

Cees chuckled and, as sternly as he could, said, “Tell Cook to make her famous chicken dish. And to go easy on the spices as Dutch folks aren’t used eating Javanese cuisine.”

Visibly pleased, Anton jumped up. “At your command, Sir!”

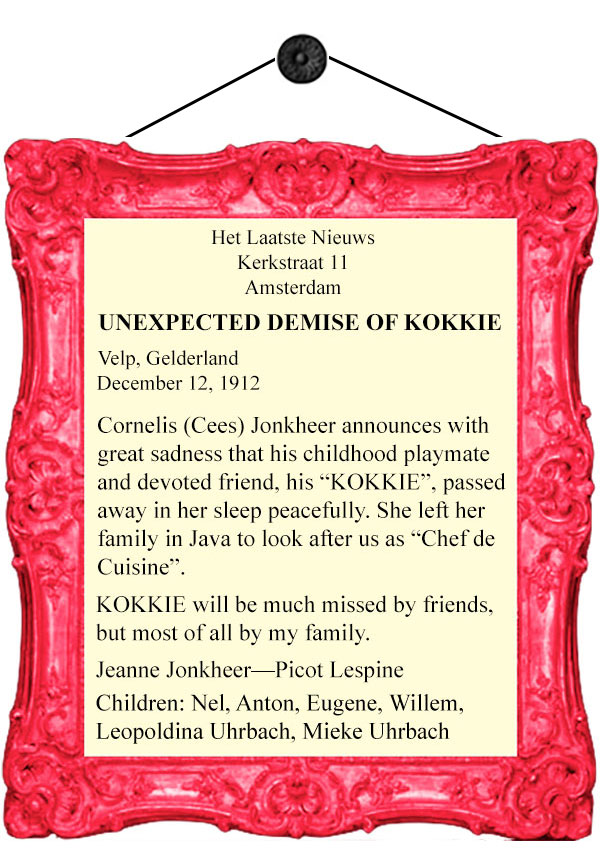

In her native Java she was Kokkie. When Mrs. Jonkheer Senior asked her to come along to her native Holland—she had not been feeling well after the birth of Anton—Kokkie accepted because she adored the baby; the thought of never seeing him grow up made her bones ache. Subsequently, she, a diminutive, brown-skinned woman, now in her early fifties, became Cook.

When Anton entered with a flourish the kitchen Cook was at the stove. With a chuckle in her voice she said, “Easy on the spices?”

“Been listening at closed doors again?” Anton sat down at the large kitchen table.

“Sunday lunch with handsome Leo a potato-eater? My delicious curried potatoes will do the trick.” Cook stirred the pot with a ladle.

Anton smacked his lips. “You know that is Father’s favorite and delicious with your chicken in coconut milk. But be easy on the sambal. Please, rice for me, Kokkie!”

“My famous fried rice for the apple of my eye,” she said with a smile.

Anton joined Cook. He put his arm around her and gave her a peck on her hair. “What will be the dessert?”

Cook cackled, imitating the parrot. She held up the soup ladle and pointed toward the door. “That will be my surprise.”

Cees did not attend the local Dutch Reformed church on Sundays but read his Bible at home. Legs crossed, Anton sat across from him, holding his Bible close to his face. Through the window behind his father’s chair he could keep an eye on the front yard.

Cook entered holding a tray with a small bottle of Genever, three glasses and a plate with fried peanuts that she put on the coffee table. She whispered in Anton’s ear that the table was ready; she returned to her domain.

Anton got up slowly and sneaked up to the cage. He put the Bible on the side table near Nel’s chair and, a finger to his lips, approached Queenie. The yellow parrot cocked its head and softly twittered. Anton pointed to the jar with nuts on the window sill and whispered, “Father. Father.” Queenie flapped her wings and screeched “Father! Father!”

Father, hearing the bird’s screeching. glanced direction cage.

“Father!” the bird cackled excitedly. Anton gave it a nut.

“Yes, Anton?” Cees took off his reading glasses.

“Cook told me the table is ready.” He took a few steps toward the dining room. “Can I open the doors?”

“No, son. You can play host next time.”

The front door bell rang.

“Hans will answer.” Cees put his Bible on the small table near his chair. He rose and joined Anton.

Hans opened the parlor door to let the guest inside.

Leopold Moojer was slender and of medium height. His thick hair was the color of honey. Clean-shaven, he had a square jaw, straight nose, a well-formed mouth and sapphire blue eyes. He entered holding a bouquet of white carnations.

Cees stretched out his left hand to take the flowers. Then he shook Leo’s hand as he said warmly, “Anton thinks highly of you. Welcome, Leo!”

Hans took the bouquet and closed the parlor door.

“Fiepjes! Fiepjes!” Queenie screeched.

Anton dashed to the cage. He fumed “Shut up” as he took the lace cloth, putting it over the cage. He turned to Leo. “Nel taught it dirty words and now Queenie bribes us. She wants her nut.”

Leo laughed and said to Cees, “When I was a child we did the same tricks. We loooved,” he chuckled, “farting in front of guests.”

Smiling, Cees poured Genever. He nodded to Anton, who took two glasses, handing one to Leo. Cees held his glass high. “Let’s drink to childhood memories!”

The trio had a wonderful time reminiscing; trying to outdo each other with stories about their wild, careless boyhood. Choking with laughter, Cees poured more Genever. Hans waved frantically from the door to the kitchen. Cees waved back. He drank bottoms up. “Anton, open the doors!”

Anton took Leo by the elbow and they went to the French double doors leading to the dining room. “You take the left, and I take the right. And when I say SESAME, we fling them open . . . to reveal a feast you will forever remember.”

Cees had sneaked up behind them and shouted, “SESAME!”

Like a pistol shot . . . the doors flung open.

Cees whistled softy. Anton’s face was a picture of surprise. Leo’s eyes were fixed on the crystal vase with white carnations flanked by two smaller ceramic vases with white apple blossoms in the center of the table.

Cees stepped between the two and entered, saying, “Cook has outdone decorating; my mother’s favorite tablecloth, used only for special occasions.” He turned to Leo. “Indeed, this is something to remember forever. Leo, you are special!”

Still eyeing the bouquet, Leo entered. He then looked into Cees’s eyes and said, voice choking, “You make me feel like family. Please, call me Poldie.” His chest heaved. “My nickname since I can remember.”

“Poldie,” Anton took him by the elbow, “I’ll show you a photograph of Father and his soldiers when he was stationed in the East Indies.” Cees was on their heels when they went to the fireplace.

On the wall was a large, framed, black and white picture. Straightening his shoulders, Cees pointed, saying, “This was my 5th infrantry. I was a colonel when I retired. My wife, Anton’s mother, was unwell. We returned to Holland.”

From the kitchen entrance Hans announced, “Mr. Jonkheer, lunch is ready.”

Cees took Poldie by the elbow and took him to the table, pulling out the chair facing two paintings. “Sit down, Poldie.” He nodded at Anton to sit facing the parlor.

“The feast can start, Hans!” Cees sat in his armchair facing Anton.

Cook entered with a platter that she put next to Cees, murmuring “Adhoo”. He laughed and said to Poldie, “Cook’s coconut chicken is everyone’s favorite.”

Hans came with the curried potatoes. Anton waved to put the dish between himself and Poldie. Cook put the bowl of fried rice next to Anton, whispering “Adhoo.”

Hans returned with a jug of beer and put it between Cees and Poldie.

“I’ll take care of the chicken.” Cees took the carving utensils. “And, Poldie, you pour the beer.”

The dishes were passed around.

“Where can I get this spice?” Poldie had dug into the potatoes. “It’s out of this world.” He mashed a potato in the coconut milk. “This is delicious, better than gravy.” He put a heap full into his mouth.

“We have friends in Java. We exchange care packages. They send us the spices making Cook and me happy and in return they get food for thought: books and magazines.” Cees waved toward the paintings. “That picture shows the island Bali and the famous rice paddies. On the right is a coconut tree. The flesh of the coconut fruit is grated and put in airtight containers. Cook also makes a wonderful coconut pudding.”

“I think that will be her surprise dessert, “Anton blurted out. “I hope she’ll serve it with her super rum sauce.”

Soon, the platters were empty.

Cees wiped his mouth, took a sip of beer, and stated, “We have had an invasion of locusts. Cook will be happy.”

Hans cleared the table of dishes and plates. He returned with dessert bowls and a saucer with berry sauce.

Cook entered with the dessert. She went to Poldie and put the dish next to his bowl. “Dutch vanilla custard!” she bragged; then she pointed at the saucer. “And your famous berry sauce.” Before leaving she whispered “Adhoo” in Anton’s ear.

The men returned to the parlor for coffee and a smoke.

They discussed the arrival of Phlip the painter. Poldie told father and son that his brother-in-law was a Sunday painter and would like to meet Phlip. The family farm at Dieren was not too far from Laren, where he had rented a furnished cottage for his sister Dina’s family.

In a jolly good mood, enjoying the company of the two enterprising men, so full of joi de vivre, Cees said, “Anton, tell Hans to get ready. We’ll take Poldie home!”

TEN DAYS LATER

Hans drove the carriage into the paved kitchen garden. He tethered the horses. Then he went to the door to the kitchen and entered.

Cook was at the table shelling peas. She looked up. Hans smiled broadly.

“I just took that painter to Boerenplezier,” Hans hee-hawed, “he wears a beret, French-type.” He sat at the table. “I thought Mr. Jonkheer would like to know what he’s like.”

“We want to know!” Anton stood at the open parlor door. “I’ll tell Father that you are here.”

Cook cupped her hand at her ear and pointed at the closed door. Hans grinned.

When Anton came back he bade Hans to enter; who left his cap on the chair.

Queenie flung herself around the cage, screeching from the top of her little lungs when she saw Hans. Cees held his hands to his ears, shouting at Anton to stop the bird’s antics. With a flourish, he took the cloth and draped it over the cage. He turned to Hans, saying that the bird recognized him as he often walked by the window, tapping the panes. Anton waved at Hans to sit down as he pulled out Nel’s chair.

Then Anton went to the chair next to his father.

“Well . . .” Cees began, “so Phlip arrived. Tell us what he’s like.”

Hans fidgeted in his chair; then put his hands on his knees. “He’s not like his relatives. According to my cousin Jan, those Zwolle folk are plain farmhands. And Phlip is showy. He wears a beret. I guess that’s how a French artist looks like.” He grinned. “Phlip got a brown beard and a moustache. He’s got not much hair left on top. I guess that’s why he keeps his beret on.” [PS 187]

Queenie chirped softly.

“He wears a city suit. Not overalls,” Hans continued. “He had a valise and a backpack with painting stuff.” He heehawed “And he carried his easel as if it’s a bishop’s crook!”

Anton looked at his father—Cees had raised his eyebrows. “Did he say anything about Boerenplezier?” he blurted out. “Phlip should be excited living in such a beautiful farmhouse.”

“Phlip kept looking around.” Hans leaned forward. “He said he would paint Boerenplezier [PS 38] and give the painting to you, Mr. Jonkheer, for inviting him. He likes painting Dutch scenes and wants to go to Dordrecht to paint sailboats. [PS 54-56] I told him to go nearby, to Zuiderzee.” [PS 76]

“What’s your impression about Phlip?” Cees wanted to know.

Hans fidgeted, eyes flitting around the parlor, and then he looked at Anton. “You have met our new milkmaid, Anneke?”

“Yes. She’s young and pretty. Well?” Anton frowned.

“I said if he needed a model,” Hans clasped his hands and looked at his boots, “that I could ask her.” His tongue moved rapidly between his lips. Then he blurted out, “But Phlip wasn’t interested in her!”

Looking at his father whose mouth had opened on hearing this puzzling tidbit, Anton snickered, got out of his chair and went to the cage. He took the cloth to unveil the bird. Queenie screeched “Fiepjes! Fiepjes!”

As if a grenade had exploded under his seat, Hans jumped up and ran out of the parlor—bumping into Cook, who shrieked “Adhoo!”

To Be Continued

February

CHAPTER TWO

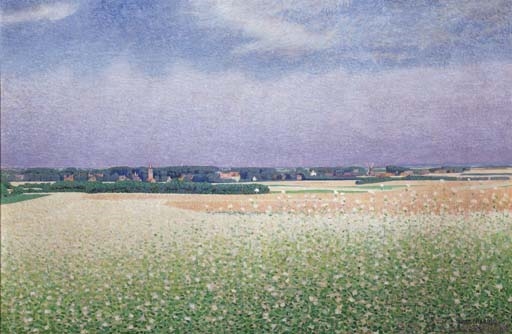

Farmhouse in Laren, Gelderland

by

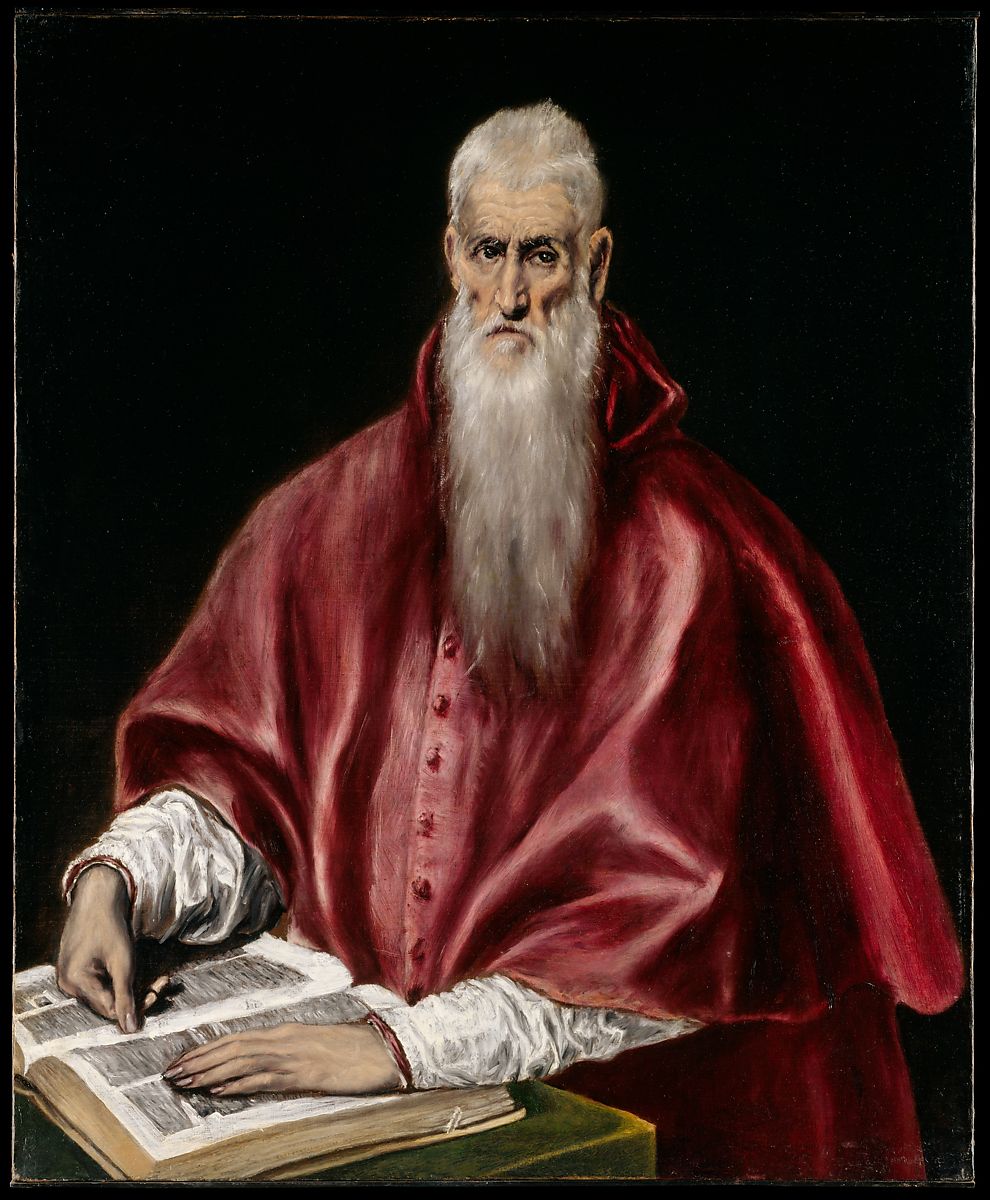

Johannes Josseaud (1880—1935)

Anneke the Dutch milkmaid

The cab came to a halt in Annastraat and Poldie got out. He walked toward the front yard. Anton came to meet him—saying he was looking forward to this adventure of exploring Dina’s cottage and, as it was a cloudless day, the trip would be enjoyable.

On the way they paid Phlip a visit. He was at his easel putting Boerenplezier on canvas; behind him stood Anneke. Anton scrutinized the milkmaid. Elbowing Poldie, he whispered to look at her. He put his hand on Phlip’s shoulder and, putting his mouth to his ear, whispered that a little birdie had informed him that this painting was a gift for his host, Mr. Jonkheer. Anton straightened, and stated that there was no hurry; he could stay until August. When the two left for Laren Phlip waved his paintbrush and Anneke, blowing Phlip a kiss, went inside the barn.

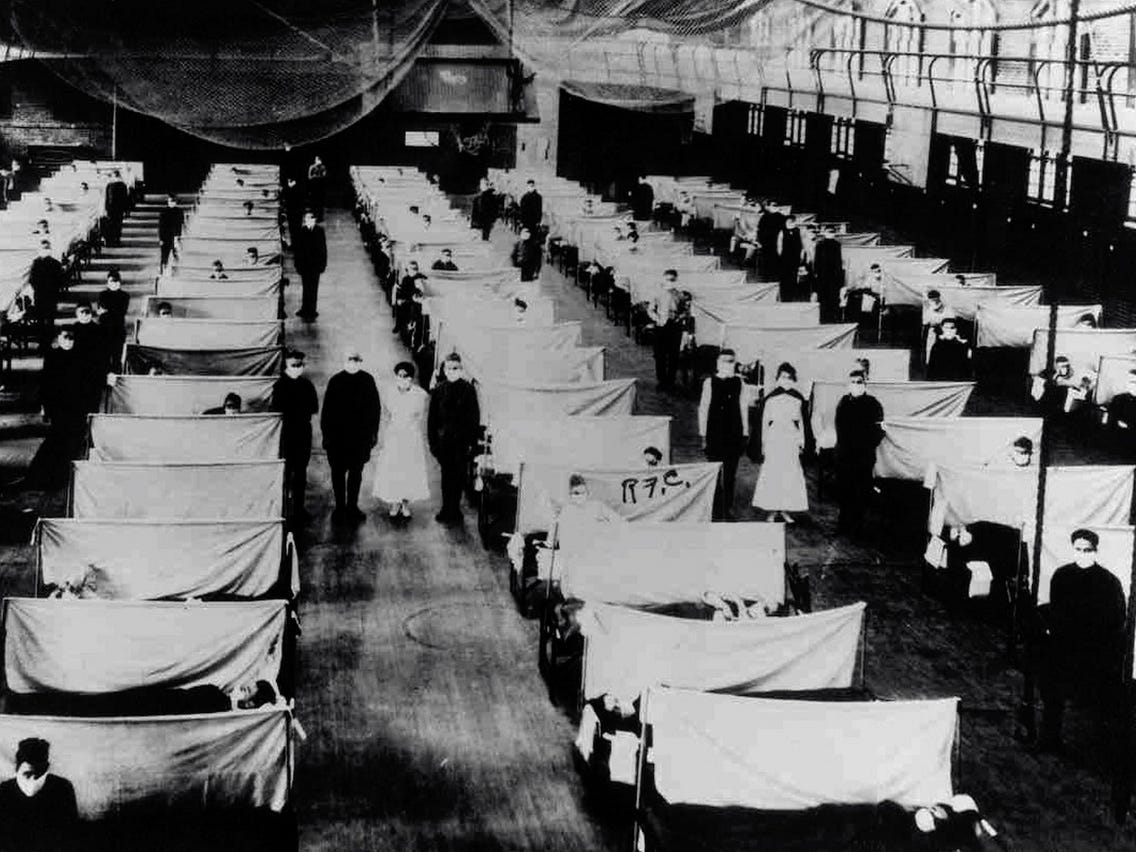

The cab took the road to Zutphen. Poldie wanted to know why he had to look at the milkmaid. So Anton let out what Hans had observed. Poldie said with a chuckle in his voice that perhaps the milkmaid was not his type? Then he said that, as he was now part of the Jonkheer family, he wanted to get it off his chest that his sister and Nicodemus had a family secret and Anton should know: Dina was pregnant with her fourth child. The oldest was a girl of six, her name was Mieke; then the boys: Nicolay, four, and two-year old Claudius. The boys could not talk properly, they had their own language. And that Nicodemus’s background was somewhat obscure; Dina had told him that her father-in-law’s family had a history of stillborn children. His sister was hoping that this child would be a healthy boy.

Anton said he would appreciate it if, on their way to their cottage, the Uhrbach family would stop at Villa Amourette. He’d serve lemonade in the front yard, beneath the apple trees, so the children could play. Poldie agreed it would be a great idea to introduce them because once in Laren the family would have a busy schedule; they would want to spend a day or two in Almelo where the couple got married in 1903. Dina, christened Leopoldina, was their father’s favorite. He had not seen his granddaughter since his last trip to Amsterdam when Nicolay was born. This autumn the family was moving from an apartment in Amsterdam to a house in Laren, ‘t Gooi.

Poldie told the driver to stop at real estate agent Frans Poos. They entered the office. Poldie inquired about getting transportation for his family; his brother-in-law liked to paint outdoors and they were looking forward to picnics at enchanting sites. The agent told them that a nearby farmer had a horse and buggy for hire. Locals delivered the daily necessities: the butcher came by; the green-grocer; the baker, and the farmer sold milk, butter, cheeses, and eggs. Poldie and Anton left with the key to the cottage.

As the cab was taking the scenic route to Laren, the two chit-chatted about country life; how healthy it was for children to roam the fields. The day that the cottage came on the market Nicodemus told him to rent it sight unseen. Poldie showed Anton a photograph of a picturesque house with dormers and a thatched roof; underneath was written in Dutch Vergeet mij niet [Forget me not]. Anton snickered, saying he was intrigued.

Arriving in Laren, a rural village, the coachman asked for directions to Vergeet mij niet. The country lane weaved between wheat fields and the carriage finally reached the cottage; it was painted a light blue and the shutters a deeper blue. Poldie told the cabby driver to return in about an hour.

Poldie and Anton walked around the upgraded farm house; Anton commenting about the blue, white and pink Forget-me-nots in earthenware pots. In the back was a large wood table and stools for eating outdoors. A small apple orchard bordered a wheat field ablaze with poppies and cornflowers; a path led to the outhouse. Poldie was aglow with praise; Nico would be in his element as painting was his heart’s hobby.

They went to the front of the house. Laughing, Poldie pointed at the Delft blue rocking chair with a blue and white seat cushion next to the door, saying he could picture his sister enjoying the view. He put the key in the lock and flung the door open. Taking Anton by the elbow, he entered, shouting SESAME!

The vestibule was tiled in brown. To the left, the open door showed the kitchen; it also had brown tiles. In the center, surrounded by stools, stood a round table and on it were kerosene lamps. In front of the large chimney facing the vestibule was a pale blue painted bench. A large cupboard held dishes. Near the window, facing the back, was a huge black range with next to it a pile of logs. On the wall, pans hung from hooks. Poldie opened the kitchen door to the yard; the water pump was in easy reach. He made sure the pump was in working order; the water was fresh and pure.

Poldie and Anton returned to the vestibule. Poldie opened the door to the room used for receiving company. The floor had black and white lozenge-shaped tiles. White linen curtains festooned the three windows. On the mantle of the white painted chimney were rows of red ceramic candle sticks. And in a half circle fronting the chimney were three ruby red velvet armchairs and two floral-print upholstered armless chairs. Small, black painted stools served as side tables. Poldie remarked that the decoration was up-to-date, and that the chairs were from a furniture establishment in Arnhem. Anton agreed that it was quality cottage-style.

They returned to the vestibule and walked up the stairs to the bedrooms. The two large ones had each a double bed and the smaller room a single bed; the covers were made of light brown linen. The wood floors had no rugs. White linen curtains covered the windows. Each room had a dresser and on the wall pegs for hanging clothes. Anton commented that it was rather Spartan. Poldie acknowledged it was bare-looking but bedrooms were for sleeping and not for lounging around: especially not on vacation.

Once more they made the rounds of the rental. Anton picked some blue Forget-me-nots and tucked them in his lapel. Elated, Poldie whistled softly as he took notes; especially about finding out who owned cottage Vergeet mij niet.

Cook knocked on the parlor door and said that Hans had information about the family of Mr. Moojer. Anton jumped up from his chair and hurried through the kitchen into the court yard where the carriage was parked. Hans gave him the message that Mr. Moojer’s family would arrive on Monday the following week. In the meantime, could he come to his office? Excited hearing that the day of meeting the Uhrbach family was near, Anton decided to see Poldie right away and Hans took him to Arnhem. They had lunch at restaurant De Schimmel; eating croquettes and exchanging news. Poldie revealed that he was going to set up a meeting with Nico and Phlip at Boerenplezier. The two painters would keep each other company so that he had his hands free. This was the season for selling real estate; he had to work!

It was Monday.

Hans set up a table and garden chairs under the apple trees. Cook draped a bright pink tablecloth embroidered with large, bright-red cherries on the table; mentioning that this was Nel’s favorite and the children would also like looking at it. Hans said it was too pretty, and then, smiling at her, he went to get a tray with glasses embossed, like confetti, with red dots and a red ceramic plate with sugar cookies. Cook got a carafe with lemonade. She looked at the inviting scene and nodded. Anton asked her to open the parlor window because Queenie liked children. Her eyes smiled as she said “Adhoo” and went on her mission; leaving the parlor door to the hall ajar as well.

Anton pulled up a chair with soft cushions for his father. Eyeing the festive table, Cees wanted to know about this impromptu party for a family they had never met. Anton evaded his father’s eyes when he handed him a glass with lemonade and began to explain that he was doing Poldie a favor—the visit would be short; the family was on their way to Laren for the summer; it was a big change from Amsterdam to country life but the children needed fresh air and discover the pleasures of nature.

With much clatter and coachmen shouting, two carriages came to a halt in Annastraat. Anton went to the gate to welcome them. Poldie was holding hands with a dark-haired girl and told him that Dina needed help with the youngest boy. So Anton introduced Mieke to his father. The girl’s hazel-colored eyes were taking in the pretty set-up. She licked her lips, winking her lashes at Cees, who smiled and invited her to take a cookie.

Poldie returned with short, stout, dark-haired Dina, a woman in her early-thirties, holding Claudius in her arms. They were followed by tall, dark-haired Nico holding hands with Nicolay. Anton made the introductions.

Poldie was pouring lemonade when Cees said to Nico, “I heard you are interested in art. I read in the Batavia Post that Theodoor van Erp just finished repairing the Buddhist temple of Borobudur. I have a friend in Amsterdam whose cousin is affiliated with the ministry of culture in Magelang, Central Java. I wonder if you know Hendrick DeBron?”

“Mina, his wife,” exclaimed Dina—she put Claudius down so she could take the glass Poldie was offering—“is my best friend!” She held up her glass as if toasting. “Wilhelmina DeBron manages Gallery Ava Riss.” Dina looked toward the parlor window. “Mieke! What are you up to?”

The girl turned around. “Can I go to the bird?”

Within seconds Anton grabbed the boys by the hand and went to the front door, saying, “Mieke, let’s say hello to Queenie.”

Cees waved at Nico to sit next to him. “Paul, Hendrick’s cousin in Jogjakarta, is a dear old friend of our family. For three generations we have served our country in the military.” He turned to Poldie. “Please, fetch the photo in the dining room so I can show Nico.”

Poldie brought the photograph. Dina and Nico were all ears and eyes when Cees began talking about the past. So he went to the parlor. Queenie was chirping softly, fluttering from perch to perch as the children whispered her name.

“I’ll see if Cook can make us lunch,” Anton said. “You stay here to keep an eye on them. If it gets unruly, Queenie is unpredictable, give her a nut.”

Anton went into the kitchen. The aroma of Javanese spices wafted from the stove where Cook was stirring in a pot. Hans was at the table cutting up cooked chicken. He joined Cook and stroked her hair. ‘You are the greatest. Everyone likes your fried rice.”

“I got jugs of beer from the tavern,” Hans said. “Lemonade is for ladies.”

The door to the parlor opened. “I’m hungry,” Mieke stated, and entered, closing the door behind her.

Cook said, “Mieke, I’ll make you something special. Come. I want to look at your beautiful dress.” The girl held up her pink skirt, showing her pink shoes, and made her entrance dancing toward Cook, who had put the ladle in the pot to free her hands. “Girls look very pretty in pink,” she said as they shook hands.

“I’m hungry.” Mieke made no bones about her kitchen mission.

“Sure. Shall I make Peef Puff Poof for you and your brothers?”

“Claudius,” she sniffed, “stinky-stinky.”

Cook raised her eyebrows. “Do you know how to change nappies?”

Mieke nodded.

“Anton,” Cook said with a straight face, “Mieke will show Uncle Poldie how to change stinky Claudius. There’s a stack of nappies on the dresser in the bathroom upstairs.”

As soon as the two had left, the parlor door opened again and Nicolay entered. He went straight for Hans who was wiping away tears because Anton had made a face at the bowl on the table. The boy stared at him in silence, and then uttered sounds as if he was in distress. “What is it, boy?”

“Peepeekaka!” Nicolay wailed. “Peepeekaka!”

Hans looked perplexed. But when Cook hollered, “Show him the toilet and make sure it’s clean when he’s finished,” he began to chuckle softly, like a hen. He took Nicolay by the hand and they left.

Cook began the preparations for the children’s meal. From the pantry she took six eggs, three bowls, a set of small bottles labeled red, green, yellow and put them on the table. Then she got three small pink ceramic plates and three small spoons. She went to the room next to the pantry, where she slept, and got a highchair for Claudius and four cushions that she put on two chairs.

She had just finished her preparations when Nicolay and Hans returned. He rolled his eyes. “I’m getting sandwiches for the coachmen,” he announced and strode for the exit door, snorting, “Peepeekaka? It’s your turn next!”

Taking Nicolay’s hand, all smiles, she made a fuss over him, and sat him on one of the cushioned chairs. She pointed a finger at her mouth, and looking into his eyes, said, “Hungry-hungry?” The boy nodded. She took his hand, and stroking his fingers, said,“Mieke-Mieke wait.” He nodded.

Nodding at Nicolay, she took a pink plate and a spoon and put them in front of him. The boy took the spoon and, laughing, waved it at her. She waved back. Blowing him a kiss, she returned to her stove to add chicken to her rice dish.

When Poldie, Claudius, Mieke and Anton entered Cook pointed at the highchair next to Nicolay. Poldie put the toddler in his seat. Eagle-eyed Mieke grabbed two plates and two spoons and gave her little brother one set and put hers on the table next to Nicolay. Then, swift as a swallow, she appeared at the stove.

“You promised to make us Peef Puff Poof,” she reminded Cook.

“Yes.” She nodded at the girl; then turned to Anton. “Please tell Father that Hans is getting the coachmen sandwiches, so he can’t help me. I will serve the rice on a platter in the kitchen picnic style. Poldie and you can clear the yard table?”

The men left, laughing, Anton saying that Father would be in his element introducing his guests to Javanese fried rice.

Cook turned her attention to Mieke. “Everything’s on the table. Let’s start.”

And she took a large fork and beat the eggs in one of the bowls until frothy. She then took a teaspoon and said, “Give me the red bottle.” So Cook put some red liquid on the spoon and dropped it in the bowl, whipping until the eggs were red.

Mieke clapped. “Is this Peef?” Cook nodded. Then she beat the eggs in the second bowl. Without being asked, Mieke gave her the green bottle. Cook whipped until the mixture was bright green. “That’s Puff!” Mieke shouted. Cook laughed. Mieke gave her the yellow bottle and Cook whipped up the last batch. “Poof!” the girl yelled.

“Mieke, over there,” Cook pointed to a small table, “is a plate with pink meringue kisses. Be careful! Put it here,” as she made space on the kitchen table.

Licking her lips, Mieke came on tiptoes and put the plate down. Then she snatched two kisses and popped one in Claudius’s mouth and the other she put on Nicolay’s plate. All smiles, the girl looked at Cook who wagged her finger.

“Now we’ll cook Peef Puff Poof on the stove. Watch me.”

Cook took a large omelet pan, lit a burner, and added butter. “See how it melts?” Mieke nodded. “Don’t let it get brown. Now, get me that bowl,” she pointed at the red one. The girl handed it to her.

Cook used a large wooden spoon to put Peef into the pan. “Get me another bowl.”

Mieke rushed to give it to her; and before Cook could ask for the last one she held up the bowl. Big-eyed, she watched Cook shaking the pan. “Oooh!” she exclaimed. “Confetti eggs!”

Cook laughed and, holding up her spoon, repeated, “Confetti eggs!”

Claudius shrieked and Nicolay beat his spoon on the table.

Cook was in her element and told Mieke to sit in her place. The children sat next to each other like parakeets as she doled out the colorful omelet when the adults entered the kitchen with the tray with glasses, carafe, and cookie plate.

“Mooke!” Mieke shouted at her mother. “Look! Peef Puff Poof confetti eggs!”

Dina rushed up to help Claudius who was eating with his fingers. Cook gave her a kitchen towel. Dina asked for the recipe.

“Mooke, I know how to make it. I’ll show you at home.” Mieke nodded vigorously.

Poldie was feeding Nicolay, saying, “This is a magic omelet.”

Anton hugged Cook; telling her that she was everyone’s fairy godmother.

Cees went to the stove and sniffed. “Fried rice!” he exclaimed. “Thank you, Kokkie!”

Cook emptied the pan in a huge, round platter and garnished it with cucumber slices. She put her delicious Javanese fried rice platter on the sideboard; next to a stack of napkins, plates, forks, glasses, and the jug with beer.

She clapped and announced, “Lunch is ready!”

While Cook and Mieke were feeding the boys, the adults were having a feast eating under the apple trees. Cees, in his element, put his arm around Poldie and said not to be formal and call him Father as he considered him part of his family.

Anton and Poldie took the empty plates to the kitchen. They returned with a tray with a coffee pot, sugar bowl, creamer, and cups. Following them was Cook shepherding the boys and Mieke holding the plate with pink meringue kisses.

“Father,” Poldie said, “I’d like to introduce Nico to Phlip at Boerenplezier. Do I have your permission?”

“Dina,” Cees addressed her, “do you think Hendrick DeBron may be interested in evaluating Phlip’s paintings?”

“Mina will,” Dina replied, “after all, she manages Gallery Ava Riss.”

“This gallery,” Nico put his coffee cup on the table, “was once owned by the antique dealer Adolph Riss. And when Antonia, the present owner, got him interested in paintings, they started exhibiting young, Dutch artists. I’m sure Mina,” he nodded at her, “will get Antonia’s ear to get involved with Phlip.”

“Ava,” Cees said, “why Ava Riss and not Antonia Riss?”

“Antonia had a child,” Dina replied, “before she married Adolph. The boy’s name is Anton Terschelling. When Adolph died she decided to rename the shop Gallery Ava Riss. You see,” Dina laughed, “her full name is Antonia, Vera, Amalia and so it became Ava Riss.”

Anton clapped and said, “I’d like to meet Anton.”

“He’s a teenager,” Dina said, smiling.

“Well, Anton,” Poldie interrupted, “how about us going this Saturday to Boerenplezier and introduce them?”

Cees nodded as he said, “You have my approval!”

The children hugging Cook, and Nico promising to visit often, they finally left.

Cees turned to Anton. “Thank you for inviting this wonderful family. I had a great time!”

When the next day a letter arrived from Het Laatse Nieuws Anton rushed to his bedroom. Two minutes later he galloped down the stairs and burst into the parlor.

“Father,” he shouted, waving the letter, “the editor wants to interview me! Here! Read!”

Face aglow, Anton went to the cage. He gave Queenie a big smile, got a nut, and holding it in front of her beak, he whispered, “Sorry, birdie. Soon I’ll be gone and no me to spoil you.”

“Anton! Anton!” the parrot yelled from the top of her little lungs, and then turned to face the street . . .

“Son,” Cees waved the letter, “this is news for celebrating.”

“Yes, Father! How about your rum punch and Cook makes her delicious corn fritters?”

“Good idea. Let’s invite Poldie for dinner.”

“I’ll go to Arnhem and make sure he’ll come helping us celebrate. And you, Father, talk with Kokkie about dinner.”

Anton hurried to catch the omnibus to Arnhem.

Hans drove Poldie to Villa Amourette. When he entered the front yard, illuminated by kerosene lamps, Cees was putting a carafe on the table draped with a red and white linen cloth.

“Good evening, Father.” Poldie put his hand on his shoulder.

“Poldie, I shall miss Anton very much but I hope you’ll keep me company, son.”

“It will be my greatest pleasure, Father,” he replied, waving at Anton who was coming holding a tray with glasses and plates; Cook followed with a platter in each hand.

“Father,” Cook said, “I also made peanut fritters.” She smiled at Poldie. “I know you like peanuts.”

Poldie took a peanut fritter. His face lit up as he was chewing. “Kokkie,” he said as he put his arm around her, “you spoil me.”

Anton laughed. “You’ll never replace me, Poldie. I’m the apple of her eye.”

Cees poured the punch into tall glasses. “Boys, help yourself,” he said, sitting down in his chair, eyeing his glass; this rum punch was his secret recipe.

While the men were enjoying themselves, chit-chatting about their futures, Cook and Hans brought dinner.

Wide-eyed, Anton looked at his father who, together with Cook, had composed the menu.

Poldie got up. “Kokkie, it looks sumptuous.” He took a satée and held it up. “How do I eat this?”

Cook handed Poldie a plate, took the satée, and with a fork pushed the chicken bits on the plate, putting the bamboo stick on the side. She smiled at him. “This peanut sauce,” she took a spoon, “is very tasty,” as she dribbled some on the chicken.

She took a large spoon, saying, “This is coconut rice,” adding it next to the chicken. “This here,” she pointed at a bowl, “is pickled cucumber. And in this bowl,” she pointed, “is a spicy ginger-red currant sauce. Which one you want?”

“Everything you cook is tasty. I want everything!” Poldie blew her a kiss.

Cees laughed. “In that case, whenever you are very hungry, come here and Kokkie will feed you.”

“Poldie, eat your heart out.” Anton snickered. “They say a man’s love goes through his stomach.”

Hans laughed loud. Giving the men a sly smile, Cook returned to the kitchen followed on her heels by Hans, still laughing.

The cheerful celebration was ending when out of the blue Anton said, “I’ve decided to leave on Friday so I can get acquainted with Amsterdam before my interview on Monday.”

Bewildered, Poldie put his fork down. “Can’t you wait until Sunday? After all, Nico is counting on us,” he said accusingly.

“Don’t worry, boys.” Cees looked at Poldie. “I’ll go with you. I’m now curious to meet this Phlip.”

It was Saturday: a sunny day.

Hans drove the landau, with Poldie in the backseat, to Villa Amourette. Cees was standing outside, eager going to Boerenplezier. Hans helped him getting into the carriage. Cook then handed Hans a hamper and bottles with punch and lemonade as well as glass goblets. He gave her a big smile and rubbed his stomach. She chuckled.

Sitting next to each other, the two men talked about Anton playing tourist in Amsterdam; Cees mentioning that Anton would need suitable rooms, and that Poldie should look for an honest real estate agent to help him.

When the carriage entered the lane to the family farm Cees took Poldie’s hand and squeezed his fingers. “I’m excited, son, to meet this painter.”

“Father,” Poldie patted his arm, “I’ve never seen you this excited. What happened?”

“I’ve an idea to surprise Anton.” Cees whispered, “It’s a secret.” His brown eyes twinkled. “But I’ll tell you because you are now brothers. If I like what he paints, I’ll commission a painting for Anton’s 30th birthday.”

“I like that.” Poldie nodded. “It will stay a secret with me.”

The carriage came to a halt in the yard; the horses whinnying.

Nico came to greet them; announcing that Phlip was in the orchard sketching Mieke, and, he smiled brightly, that he had a surprise in store for them.

Greeting Nico, Hans scampered past them carrying the hamper. Anneke followed him with a brown terrycloth blanket and a large, soft pillow for Cees to sit on; Cook had thought of everything.

Poldie wanted to know if he had seen the painting of their farm.

“Phlip told me that he likes to sketch his object first, with a soft pencil, until it’s perfect,” Nico said. “He then takes a brush painting in the colors. I’m sure Boerenplezier will be wonderful when finished because I have looked at two of his paintings with scenes of Paris. He hopes to sell these here.”

Nico took Cees by the elbow; Poldie followed them.

“I want you to meet a painter I met at the post office in Laren,” Nico continued. “Johan Josseaud insisted coming along when I told him that I was on my way to meet Phlip. Mieke also wanted to meet Phlip. Let’s join them.” He laughed.” Our artists are having a competition sketching Mieke.”

Anneke was putting the red and white tablecloth on one of the five picnic tables in the cherry/apple orchard while Hans opened the hamper that stood on a bench.

“Faty!” Mieke waved at her father; she was sitting on a table.

Phlip and Johan looked up from their sketchbooks. When they saw the threesome approaching they stood.

Taking the pillow and blanket, Anneke came over. She put the pillow on the armchair behind Mieke; whispering that the girl should come down and greet Mr. Jonkheer.

Nico introduced Johan. Cees nodded at Anneke who was draping the blanket on the bench to the left of the chair. She curtsied and joined Hans.

Cees settled in his chair. He invited Phlip to sit on his right with Johan. Turning to Mieke, he smiled and said she should sit next to him on the blanket with her father and Uncle Poldie.

“Phlip,” Cees said, “I’d like to have a look at your two paintings of Paris so I have an idea about your artistic abilities.”

Phlip looked at Nico, who nodded, and he left for the farmhouse.

“Look at my sketches!” Mieke showed the ones Phlip and Johan had made.

Chuckling, Cees took them and scrutinizing one, he gave it to her, saying, “I like this one best.”

Gleefully, the girl pointed at Johan. Poldie and Nico laughed.

Phlip returned carrying two canvasses. He sat next to Cees, saying, “This is Place de Clichy,” [PS 5] as he gave him the painting.

“I like it!” Cees nodded as Mieke peered over his shoulder. “Have a look.” He handed the painting to Poldie and Nico. Johan had joined them.

“And this is my favorite.” Phlip gave Cees the other one. “Place Pigalle.” [PS 49]

“It’s as if I’m sitting at a window, looking out at this busy, lively square.” Cees smiled. “I like your art work, Phlip.”

Johan had joined Mieke, looking over Cees’s shoulder. “A photograph can’t do justice to this stimulating scene,” he said. “I haven’t been to Paris but I feel the excitement that we lack in Amsterdam where I was born and have lived all my life.”

“Nico,” Cees said, “Dina should tell Mina to sell them at the gallery. Amsterdammers will acquire them, wishing to visit Paris. If I were younger, I’d certainly plan on going.”

“Art gallery, which art gallery?” Johan looked eagerly at Nico for an answer. “Perhaps I can show some of my work as well?”

“Good idea,” Poldie said and, taking Mieke’s hand, he went to the table where Hans had laid out the snacks, punch and lemonade. Uncle and niece became a duo: Uncle playing host and niece, following his orders, was hostess. In no time, the hamper was empty!

Having fun, the girl put her arms around Cees’s neck, and whispered that she liked him a lot. In his element, Cees said she should call him Father. They were one big family.

Carrying the hamper, Hans scampered past the party towards the yard.

Cees rose and, nodding at Poldie, announced that it was time to go home.

The carriage came to a halt at Villa Amourette. Cees told Poldie that he was in a hurry: he wanted to write the letter regarding the painting for Anton’s 30th birthday. They embraced. Hans drove Poldie home.

Quickstepping into the hall, Cees made a beeline for the secretary in the parlor. He opened it and took the inkstand as well as some sheets of letter paper. He then went into the dining room and put them on the table. Softly whistling, he took from the buffet a wood tablet.

Cees sat in his armchair. He put the tablet in front of him, the inkstand on his right and the letter papers to his left—then took a sheet and put it on the tablet. Smiling, pen in hand, he looked at the paintings on the wall.

Cees Jonkheer was ready to compose his letter to Hendrick DeBron.

To Be Continued

I have the structure worked out

I need only set the lines to it

MENANDER

March

CHAPTER THREE

HOUSE IN VELP, GELDERLAND

OLGA’S FOUNTAIN PEN

Villa Amourette

Velp, Gelderland

July 6, 1911

Dear Hendrick,

Your cousin Paul was a dear friend of my family. We, three generations serving our country in the military in Semarang, often visited him in Jogjakarta. Paul took us sightseeing and the reconstruction of the Borobudur truly is his crown jewel.

Hendrick, I have a request.

A few days ago Nicodemus and Leopoldina Uhrbach and their children, on their way to Laren for a two-month vacation, were here for lunch.

As you know, Nico is an ardent Sunday painter. It so happens that I have sponsored a 25-year-old artist presently lodging at my farmhouse in Dieren. Phlip Goudsmit was born in Zwolle but at age 6 his parents moved to Paris. Nico was eager to meet Phlip and I promised a rendezvous at Boerenplezier.

During our conversation Dina told me that your wife Wilhelmina, who manages a prominent art gallery, Ava Riss, in Amsterdam, is her best friend. Needless to say I felt connected, because Poldie, her younger brother, is my son Anton’s best friend. Poldie calls me Father, we are that close. Anton’s mother passed away 17 years ago. I remarried and Jeanne and I have a 15-year-old daughter, Cornelia. They are in Den Haag visiting relatives as Nel is very pretty and had an ardent admirer my wife didn’t think was suitable. Nico mentioned Willem, your son. I hope he is giving you joy, and will follow in your footsteps.

I just returned from our rendezvous at Boerenplezier, and I can tell you that Nico and Phlip are best mates. Nico intends to paint there often under the guidance of Phlip.

At the picnic lunch in my orchard, Dina and the children were at their charming cottage Vergeet mij niet, Nico mentioned two paintings Phlip took along; he wants to sell them. I very much like the Paris scenes. When the family was at Villa Amourette I had asked Dina to ask you to evaluate his work. However, she said Mina will ask the owner of the gallery to appraise the paintings.

The end of May Anton returned from Paris; it was my 25th birthday present. He told me this Paris trip is unforgettable because it inspired him to become a literary journalist. Next week he has an interview with the editor of Het Laatste Nieuws.

Anton’s favorite author is Stéphane Mallarmé whose poem The Afternoon of a Faun was set to music by Debussy.

Hendrick, this is strictly confidential. For obvious reasons Mina and Dina are not to be involved. I want to commission a painting by Phlip of The Afternoon of a Faun [PS 329] for Anton’s 30th birthday. The painting will be purchased by you. I shall contact my bank to contact you directly regarding the financial transaction.

I will be exceedingly grateful if you consent to this request: A surprise for my son Anton.

With sincere and warm greetings,

Cornelis

Cees reread his epistle twice. He addressed the envelope to Mr. Hendrick DeBron, Herengracht 56, Amsterdam. Then he nodded, looking at the two paintings, saying to himself, “Where shall I put up Boerenplezier?”

Cees got up, walked to the hall and entered the lavatory. He ran the tap and, sealing the envelope, spat in the air for good luck. Then he put the letter on the silver tray on the hall table for Hans to mail.

A telegram arrived from Anton on July 9th.

Hans entered the kitchen and waved a letter. Cook said she would give Father the much awaited news. She knocked on the parlor door and entered. Sitting in his armchair, Cees held out his hand. All smiles, Cook gave him the letter while whispering “Adhoo”, and left.

Cees got up, walked to the secretary and took a letter opener. He returned to his chair to read Anton’s letter.

Dear Father,

My promised letter will be short. I’m eager to tell you vis-à-vis about my interview with Albert Heyn, the editor.

Albert was going to interview Joshua Schwartz, the novelist son of Cornelia van Vollenhoven. Joshua was born in 1858 in Amsterdam and took the pseudonym Maarten Maartens. He wrote a detective story in English: The Black Box Murder. Imagine, Father, Albert decided to test me! So now I have the privilege to interview him on Tuesday, the 16th.

This Friday I’m taking the late afternoon train.

I’m looking forward being home with you, Father.

Your loving son,

Anton

It was Friday

When Anton arrived at the station in Arnhem Poldie was on the platform to welcome him. While driving to Villa Amourette the young men had a serious conversation on how to prepare Father for the imminent transport of Anton’s belongings to Amsterdam. Poldie advised Anton to be discreet when packing, and suggested Cook give him a hand; he should listen to her because she knew how to soothe Father when his feathers were ruffled. He had employed a moving company he had used in the past, and had set the date for Tuesday. He would be on the premises to supervise the transaction.

When the carriage arrived at Annastraat Cees was standing at the gate. He waved and smiled when the two approached him. After a warm welcome, they went inside.

Poldie decided to pay Cook a visit. She was thrilled to see him and right away announced that she’d make fried rice. She winked when she said that this dish always put Father in a good mood. Poldie gave her a hug, and left for the parlor.

Cees sat in his armchair chatting with Anton, who sat across from him in his usual chair, but when Poldie entered he stopped talking and waved at the chair next to him. Poldie rose to the occasion to play favorite son.

“Isn’t it wonderful news?” Cees waved the letter he kept on the side-table. “Anton will have the honor to interview this famous Dutch novelist on the day he starts working at the newspaper.”

Queenie twittered beneath the cloth.

“Lady Luck is with Anton,” Poldie said as he took the letter. “Has this detective story,” he asked as he read, “been translated into Dutch?”

“Good question,” Anton replied. “I’ll ask the novelist. And if it hasn’t been translated yet, I’ll inquire about a super translator.”

Cees clapped. “Bravo! I like your spirit.” He rose. “Let’s toast to that!” He went through the open doors to the buffet in the dining room. “I need help.” Cees smiled when he saw the table set for three.

Poldie winked at Anton and they joined him.

Cees poured the gin. Holding their glasses, the threesome returned to the parlor.

“How about going to the farm tomorrow and say hello to Phlip?” Poldie suggested.

“How about a picnic in the orchard and Cook”, Anton raised his voice, “will prepare her special orchard hamper. Father, we’ll sip your rum punch.”

“I’m game!” Cees held up his glass. “You two come up with great ideas.”

Queenie cackled softly.

Poldie snickered as he went to the cage. He whispered, “Queenie, soon no Anton to ruffle you. Have a last look at him,” and he removed the cloth. The parrot went to her top perch and faced the street. “Okay,” Poldie said, and covered the cage.

Cook announced from the open door, “Fried rice is on the table.”

“More to celebrate!” Cees got up, and holding his glass went straight for the buffet for a refill; glancing at the large platter and a dish with cucumber salad.

As they ate with gusto, Cees suggested that Poldie stay overnight on Saturday.

The carriage came to a halt in Annastraat. Poldie got off with his duffel bag, smiling at Hans, saying he was looking forward to the picnic. When he opened the gate Anton got up and Cees waved. Father and son were having coffee and Poldie sat down, saying he already had two cups at his lodgings. Anton suggested he show him to his room.

As they entered the house, Cook came holding a newspaper, telling them that Hans was on the way to the farm delivering the hamper. With a cackle, she went to bring Cees his gazette.

Cees was hiding behind the paper when Anton and Poldie returned. They sat down and spoke in low tones about the upcoming event. Folding the newspaper, Cees put it on the table, saying it was time to go.

Anton went to the kitchen to tell Hans they were ready. He gave his Kokkie a hug, saying he was excited about becoming a journalist. He would miss her very much. She wiped away a teardrop and nodded.

The threesome, Cees was in a jovial mood and had linked arms with his “sons”, waited for the carriage. When Hans drove up they cheered. The horses were festooned with ribbons and little bells tinkling: announcing the start of a cheerful day at the farm.

Upon arrival, as Anton was giving his father a hand descending the carriage, a teenage girl linking arms with an old woman holding a basket with eggs entered the yard; passing them, the girl smiled and they went toward the orchard.

Hans said with a chuckle, “That’s Anneke’s younger sister and their grandmother. The old woman raises chickens. On holidays she sells capons and makes a small fortune.” As he took the carriage toward the stable, he announced, “Anneke takes care of the food.”

Anton shouted after Hans, “Raising capons is more lucrative than selling eggs?”

Hans shouted back, “I told you, a small fortune!”

Cees shook his head. “Let’s go!” he said, marching toward the orchard.

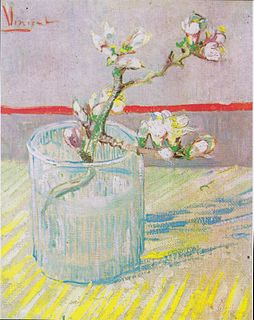

ALMOND BLOSSOMS

“What would life be if we had no courage to attempt anything?”

Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890)

Phlip was at a table sketching Mieke. Johan, at another table, was looking intently at an apple blossom.

[PS 87] Anneke was posing for Nico under the watchful eyes of Dina at another table.

When Cees saw the group he stopped. “Anton! Poldie! We have company!” He waved at Nico, who had turned his head upon hearing his voice. With a huge smile of surprise, Nico rose from the bench, holding his pencil, and shouted, “Cees!” He rushed up when he saw Anton and Poldie.

Mieke jumped from the table, running toward Cees, shouting, “Father!”

Phlip and Johan also came to greet them.

Anneke went to the table on which stood the hamper. Dina followed her.

“Why didn’t you tell us the family was coming?” Dina said, frowning.

“Missus, I thought the food was for your family,” Anneke replied. “Hans said he wants to learn sketching. That’s why I take care of the hamper.”

Dina turned around and with outstretched arms greeted Cees.

They all went to Nico’s table. And facing each other, sat on the two benches. Cees asked Poldie to get him an armchair from the house.

Anton joined Anneke. They brought the refreshments: lemonade and rum punch.

Poldie came with the chair. Cees held up his punch glass. “Anton is leaving Monday for Amsterdam,” he said. “He is a journalist employed at Het Laatste Nieuws.” He looked at Phlip. “He wanted to say goodbye.”

Poldie clapped. “Let’s drink to Anton’s success as a journalist.” He raised his glass. “And that Phlip becomes a famous artist.”

Mieke went to Phlip and, raising her glass of lemonade, said, “If you are famous, will I also be famous?”

They all laughed.

When Anneke saw her sister and grandmother now carrying cherries in her basket, as well as Hans holding a cage, she rushed to meet them. Hans went to the table near the hamper.

“I want to talk to granny,” Cees said to Poldie.

Poldie escorted Anneke and her family to meet Cees.

“So,” Cees said, “you are the egg provider at my farm.” He nodded at granny. “Excellent eggs.” Then he turned to Anneke. “Your sister. What’s her name?”

“Teuntje, Mr. Jonkheer.”

Cees smiled. “Short for Antonia?”

“Yes, Mr. Jonkheer. Teuntje is fifteen.”

Cees pointed at the table where Hans sat. “Anton, invite them for lemonade.” He put his

arm around Mieke and said with a chuckle, “Yes? You want to tell me something?”

The girl’s eyelashes fluttered like butterflies. “I’m hungry,” she stated, pointing at the hamper.

“Is that so?” Cees raised an eyebrow. “You want to see what’s in the hamper?”

Mieke bobbed her head.

“I’m curious too.” Cees gave her a wink. “Ask Anneke if you can help. And if Cook has made her famous curry eggs, bring me two, right away,” he gave her a push, “because I’m also hungry.”

When Mieke asked Anneke to open the hamper, because Father wanted to eat eggs, Anneke asked Teuntje to help her. She looked toward Cees’s table as she unfastened the lid, softly reciting, “Aba, abe, abi, abo, abu.”

Mieke laughed and clapped. She looked at the containers, wondering aloud, “Where are the curry eggs?” She gave the top box to Anneke who, upon opening it, announced, “Ham sandwiches.” The next boxes contained cheese—and liverwurst sandwiches. At the bottom was a flat box labeled ‘Father’. Elated, Mieke opened it. “Curry eggs and chicken pieces!” She dipped a finger in the brown sauce and made a face.

Teuntje handed Mieke a plate and, on the girl’s order, Anneke put on it two eggs and some chicken with brown sauce. “Wait for Teuntje.” She gave her sister a napkin as well as a fork and knife. “Now bring Father his curry eggs,” she said with a big smile. “And Teuntje, ask the adults to come here and get their sandwich. I don’t know what they prefer.”

When Mieke put his plate on the table Cees exclaimed, “Chicken Bubby! That’s a treat I haven’t had for a long time.”

Mieke made a face. “I don’t like that sauce.”

“Soy sauce. I like it.” Cees took the napkin and utensils from Teuntje.

“Anneke asked me to invite you to the hamper,” Teuntje announced. “And please choose a sandwich.”

Laughing, Nico, Dina, Poldie, Anton, Johan, Mieke and Phlip joined Anneke. After some jostling, they returned with their sandwich.

“Poldie! Are there any left?” Cees nodded at the table where granny, Teuntje, Anneke and Hans were enjoying lemonade.

“The liverwurst sandwiches were not a favorite.” Poldie raised an eyebrow.

Cees clucked his tongue, and with a grin, he said, “Cook once told me that Hans likes liverwurst sandwiches. Go over and invite them to eat.”

The guests waved toward Cees when they went to the hamper.

Poldie took the punch bottle and putting it next to Cees, whispered, “How did Cook know to make four?”

With a short chuckle, Cees replied, “Ask Hans, our oracle of Dieren.”

Anneke came over and held out her hand, saying, “Come with me, Mieke.” The girl jumped up. They went to granny’s table. Teuntje took handful of cherries from the basket and put them in the empty sandwich box. “Can you bring these to Mr. Jonkheer?” All smiles, Mieke bobbed her head. “And please thank him for the delicious treat enjoying a sandwich here.”

Mieke nodded and, holding the box as if it contained a delicacy, went on her mission. “Cherries from granny to say thanks,” she said as she put the box on the table.

“Well . . . thank you, Mieke.” Cees waved in the direction of granny.

Anton rose and blew granny kisses.

Hans came to see Cees. “These cherries are the last from a special tree near our kitchen. Granny likes making cherry wine.” He looked at Anton. “Don’t worry; we have more. I’ll drop off a basket tomorrow.”

Poldie joined Hans. He said in a low tone, “How did Cook know to make four?”

Hans grinned, took off his cap to scratch his head, and rather casually said, “Cook always makes me four. I’ve a big appetite.” He put his cap back and turned to Cees. “Mr. Jonkheer, are you going to watch us getting lessons from Phlip, or shall I take you home?”

Cees looked bewildered at Phlip. Then he turned to Hans and said, “Of course we stay and watch. But first let’s eat the cherries.”

Flanked by Anton and Poldie, Cees settled in his armchair; watching, and listening as Phlip instructed the aspiring artists.

“Do you want to sketch your daughter or Teuntje?” Phlip asked. Dina was busy wiping Mieke’s hands and face, cherries are juicy, so Nico resolutely said, “Teuntje”.

Johan said he wanted to sketch Anneke.

Hans said, “I’m going to draw a chicken.”

“And I’m going to immortalize granny. She’s such a kind soul,” Phlip said as he rose.

That settled, the artists, carrying a sketchbook and pencil, went to their designated tables.

Mieke strolled over to Phlip sketching granny; straight as a rod, looking intently at the artist, she eagerly sat for her portrait. [PS 13]

“Why not sketch me?” Mieke asked. “I thought I’m your favorite.” [PS 65]

Phlip replied, “I’ve done your portrait many times and I want to please granny so she has a souvenir of this happy day.”

Biting her lip, Mieke nodded, and left to pay Johan a visit. Anneke looked very pleased; the artist was drawing her standing. She lifted her skirt to show her shoes.

“Why not sketch me?” Mieke demanded to know.

“I did the other day,” Johan stated, “and it was better than Phlip’s portrait.”

“I also liked it better,” Mieke acknowledged. She went to watch her father sketching Teuntje’s portrait. Her mother stood, talking, behind him. She interrupted the conversation. “Faty, why don’t you sketch Mooke?”

“Phlip said to sketch Teuntje,” Nico pointed at his sketchbook, “because your mother I can sketch any day.”

Mieke took her mother’s hand, and they went to look at Hans drawing his chicken model, standing in the cage. Dina said, “It’s very plump. What kind of chicken is that, Hans?”

“A capon,” Hans said with a grin.

“What’s a capon?” Mieke wanted to know.

“A lazy chicken. Look,” Hans pointed at granny, “how happy she is getting all his attention.”

Dina stared at the chicken, then at granny. Nodding, she took Mieke’s hand and went straight for the table where Cees was having a feast talking to Anton and Poldie.

Cees clapped to get attention. “I want to see your sketches, and Anton wants to say au revoir , and then we go home.”

Mieke made a beeline for Phlip. She told granny that “Father” was leaving and that Phlip should come and wave. She took his sketchbook and went to summon Johan. Meanwhile, Dina ordered Teuntje to get the hamper ready for Hans as they were returning to Villa Amourette.

Cees looked at Johan’s sketch of Anneke. Nodding, he approved; the milkmaid showed more than her shoes.

Nico hesitantly showed his portrait of Teuntje. “It’s not up to your expectation, I know,” he said. “I’m not good at drawing people.”

“I recognize her,” Cees said, “and that’s what counts.”

Mieke gave him Phlip’s sketchbook; the artist stood next to Anton.

“Granny!” Cees was all smiles. “That’s her, all right! Excellent!”

Anton patted the artist on the shoulder.

Hans approached and announced that the carriage was ready. Anton shook hands with Phlip and wished him all the best in the world.

Shouting au revoir, they waved when the landau with Cees, Poldie, and Anton left for Villa Amourette.

Upon arrival, Cees said, walking to the gate, that he was tired, and would meet them in the parlor for a drink, and after dinner, a talk.

Anton and Poldie went to see Cook.

“Thanks for the delicious ham sandwiches,” Poldie said as he winked at Anton. “What are you cooking for dinner?”

Anton put his arm around his Kokkie. “Father liked the chicken in soy sauce. He needs something very special to cheer him up because I’m leaving on Monday.” He gave her a squeeze. “Father mentioned he would talk after dinner. Do you know what that means?”

“He’ll give a speech.” Cook nodded. “He’s a military man. They like routine. I know his habits.” She went to a small crate near the exit door of the kitchen. “In the old country he liked fish in ginger sauce. Hans knows a fisherman, and I asked him to get me a large fish. This one,” she opened the crate, “is from Zuiderzee.” On a lump of ice sprawled, grey eyes wide open, a very large fish.

Shaking with laughter, Anton and Poldie embraced Cook.

“Don’t worry,” she whispered. “He’ll be in a very good mood after dinner.”

When Anton and Poldie entered the parlor Cees was sitting in his chair sipping gin. Two glasses were on the coffee table. He waved at them to take a glass, saying, “Cheers!”

“Cheers, Father!” Anton and Poldie raised their glasses.

“Sons, I’ve a problem. Where do I put up the painting of Boerenplezier?”

“How about”—Poldie pointed at the wall above the secretary that stood between the doors to the hall and the kitchen—“putting the family photograph”—he pointed at the fireplace to the right of Cees—“above the mantel?”

Anton went to the secretary. He removed the framed photograph, took it to the fireplace and put it on top of the mantel. He sat in Mother’s chair and said, “Mother can now see her family close up.”

Cees looked at the wall above the secretary. “Excellent proposal, Poldie,” he said. “You fixed my problem.”

Cook entered and went to Cees. She whispered in his ear; it was a magic word because his face lit up, and he shouted, “Unshoonghee!”

Cackling, Cook left.

“Isn’t that fish in ginger sauce with vermicelli noodles, Father?” Anton rose to help him out of his chair. Linking arms, they went into the dining room; Poldie followed, having fun he cracked his knuckles.

On the table, to the left of Cees’s seat, on a large platter, bedded on a mountain of noodles, were crisply-fried chunks of fish. In front of the stack of plates was a large sauceboat with steaming hot ginger sauce. Anton pulled out the armchair for Cees. Then he sat across from him. Poldie sat in his designated chair.

“This smells awesome.” Poldie inhaled the aroma.

Cees put a chunk of fried fish and a heap of noodles on a plate and handed it to Poldie. “The sauce is spicy, so be careful,” he said, moving the saucer towards him. Then he served Anton. Face aglow, he put the choicest piece of fish on his own plate, adding plenty of noodles, and then drenched it with sauce. “Bon appétit!” he said, tucking into his Unshoonghee.

When Cook came to clear the table she saw fish bones for the cat and a clean sauceboat; as if the cat had licked it. She whispered “Adhoo” in Anton’s ear. He gave her a wink.

“Coconut cookies for dessert,” she announced. “Shall I serve the coffee here, Father?”

“You are spoiling us, Kokkie,” Cees said. “I can’t move. We stay here. Anton, let’s play rummy. The cards are in the bottom drawer of the buffet.”

Anton looked at Poldie—who, mouth open and eyes bulging, stared at Cees.

“We used to play rummy with my brothers when they were still living here,” he said in a low voice, and got the playing cards.

“I’ll deal.” Cees shuffled the cards. “Seven cards each.”

When Cook brought the coffee and cookies Cees was in a great mood: smiling, shouting, dealing the cards. She nodded at Anton, whispering in his ear, “I told you so.” She left all smiles, saying to the ceiling “Adhoo.”

When the hall clock struck eight . . . Cees got up. “I’m going to bed. Anton, Poldie,” he nodded at them, “we’ll talk about money matters tomorrow.”

TO BE CONTINUED

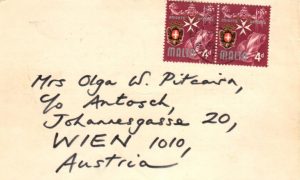

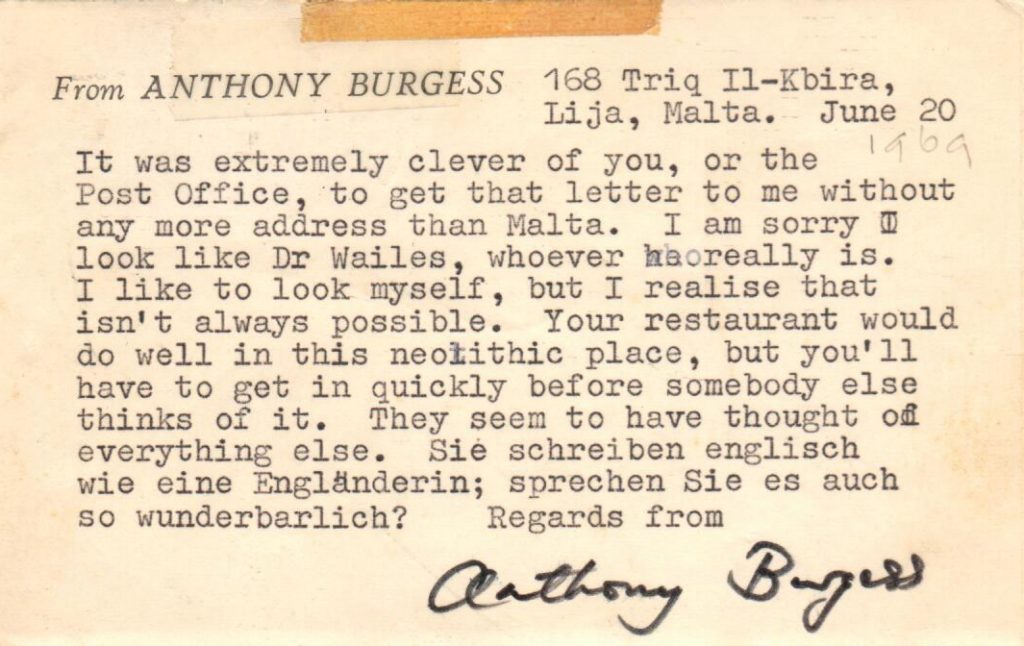

MALTA

ANTHONY BURGESS, Author

(1917-1993)

The house was bought by Burgess in 1968

168, triq il-khira—Lija, Malta

Date: June 20, 1969

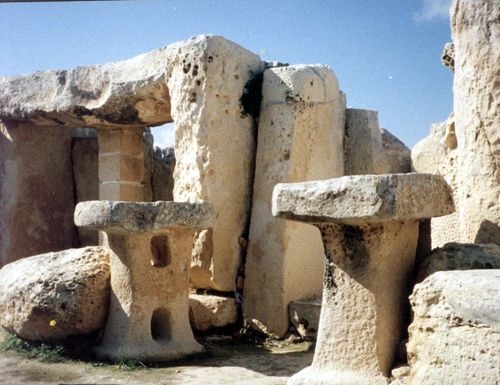

MALTA: OPEN AIR DINING

April

CHAPTER FOUR

RIJKSMUSEUM, AMSTERDAM

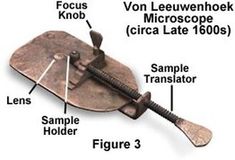

Rembrandt, in full Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, Rembrandt originally spelled Rembrant, (born July 15, 1606, Leiden, Netherlands—died October 4, 1669, Amsterdam), Dutch Baroque painter and printmaker, one of the greatest storytellers in the history of art, possessing an exceptional ability to render people in their various moods and dramatic guises. Rembrandt is also known as a painter of light and shade and as an artist who favoured an uncompromising realism that would lead some critics to claim that he preferred ugliness to beauty.

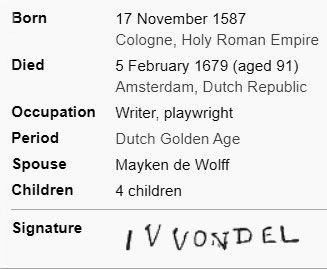

JOOST VAN DEN VONDEL

It was Sunday

Anton opened his eyes. Bird-chatter floated through the open window. A smiled hugged his lips as he listened to their chirping. Then, with a jolt, he sat up. “Money matters,” he whispered. “Will Father interrogate me?” He put his feet in red velvet slippers, Nel’s birthday present, and went to the window. He drew the curtain aside and leaned out. Inhaling the fresh air, his eyes focused on the small green apples on a nearby branch; two finches looked at him.

“Anton,” Poldie said in a low voice. “Anton.” He stood at the guest-bedroom window.

Startled, Anton smiled. “Oh! Good morning, Poldie. We’ll start packing after breakfast?”

“How about discussing the important issue?” Poldie rubbed his thumb and index finger.

Anton’s face lit up. Then he, too, rubbed his thumb and index finger; and now smiling broadly, he said, “Come on over! Two heads are better than one for planning.” He put on his dressing gown and left his door ajar. Softly whistling, he arranged a stool and chair near the window. When he opened a drawer of his nightstand, to get a tin with biscuits, Poldie entered wearing pajamas and shoes; excusing himself for not having packed a gown. Anton took off his, and invited Poldie to sit in the chair as he took the stool. He held out the tin; in silence they munched biscuits, looking at each other.

The door opened. “Coffee,” Cook whispered. Poldie went to get the tray with two steaming mugs, and blew her a kiss. He closed the door firmly.